Publication

Article

Pharmacy Practice in Focus: Oncology

The Democratization of Adverse Drug Event Reporting: The Movement Toward the Patient Experience and Individual Wellness Goals

Author(s):

To help patients live the best possible life with their condition, we ultimately need to look beyond clinical trial data toward new and emerging sources of information that highlight the real world, longitudinal experience of a broader and more diverse patient population.

“Do you have any questions for the pharmacist about your medication?”

This is a question patients are commonly asked when they receive their prescription bag. They may respond by asking how many times a day they should take a medication or when to take it. Those are the easy-to-answer questions.

Often, however, much more complex questions arise. Sometimes this is because patients have read about a medication on the Internet and, armed with the information they’ve found, have concerns about how it may truly help or harm them. Then there are the patients taking specialty medications or those living with comorbidities. Answering questions in these more complex cases requires pharmacists to dig for more data. All too often, we’ll default to providing information from a trusted drug information source, like the product label or drug information database. This information details the impact of a medication on a clinical endpoint in a well-defined, disease-specific population (eg, initiating insulin typically decreases glycated hemoglobin by 1.5% in patients with type 2 diabetes). However, these resources include many limitations and caveats that may cause more confusion if we explain them. If we can’t find the information easily, our response may be to suggest the patient check with the prescriber.

Although pharmacists have access to a wealth of drug information gleaned from clinical trials that they can share with patients, the reality of clinical trials is that only a few hundred or a few thousand people, at most, can participate in them. Whether a generic drug or a specialty medication with high-risk/high-reward potential, each medication affects each patient differently. Clinical trial endpoints do not always align with what’s important to an individual patient’s goals. Not only do patients want to just monitor their lab reports, they want to improve their health-related quality of life (QOL) and overall wellness, and each patient has his or her own definition of how acceptable an affect is on their QOL. If we’re going to be more patient-centered, we must start examining how we can tailor our responses to address patients’ particular situations and the realities of how medications are taken and experienced outside of a clinical trial.

Medications in the Real World

Although clinical data can give us good baseline information about a medication, this data is gathered within the 4 walls of a pristine medical environment. Clinical trial participants are not representative of the actual populations of patients who will take a medication beyond those 4 walls. That’s not only because the number of trial participants are limited, it’s also because, once products are in market, new information sources from post-market studies or individual reports are limited and significant updates are slow and sparse. Once a product is approved, the FDA relies on spontaneous reporting or large claims databases to learn about new adverse events (AEs), but these only give a snapshot based on an individual’s experience with a drug. This snapshot is just that: a small window into what some people experience in a brief period of time. It gives little insight into the patient experience of taking a specific medication over time.

Information sources also typically lack any information about the patients who are using medications for off-label indications. This is an important omission given how often patients are doing so in the real world. More than 1 in 5 current outpatient prescriptions written in the United States are estimated to be for off-label use and nearly 75% of these uses have little or no scientific support.1 For example, the patient information leaflet for amitriptyline contains information from clinical trials in patients with depression conducted more than 50 years ago. Yet, we know that today, amitriptyline is rarely prescribed for depression. Patients are much more likely to be using it for insomnia, neuralgias, or migraines. Some patients are even using it specifically to treat side effects, such as to control excess saliva.

In another example, the rates of nausea among patients with Parkinson’s disease in some clinical trials of levodopa-carbidopa were as low as 3%.2 These trials were conducted in patients with a relatively recent diagnosis who were taking low doses of the medication. What’s the issue? Patients at a more advanced stage of the disease typically take much larger doses than those patients studied in clinical trials. Also, some patients with Parkinson’s develop gastroparesis as the disease progresses, leading to variability in how the medication is metabolized and significant changes in the pharmacokinetics of the medication. The side effect information from patient populations enrolled in clinical trials with standardized dosing protocol, no comorbidities, and more recent diagnoses aren’t likely to be generalizable to many patients taking this medication.

The manner in which AEs are collected in clinical trials could also contribute to an overestimation of the problems patients are actually experiencing. For example, the package insert for the immunosuppressant Prograf (tacrolimus) states that nausea occurred in 38% of patients.3 However, when looking at patient reports of side effects on PatientsLikeMe, a website where patients living with chronic conditions track their health, connect with others, and contribute data for research, there are only 4 reports of nausea from 192 patients, or about 2%. The difference may be clear to anyone who has spent time with a patient who has recently received an organ transplant. It’s common to experience nausea, but the nausea is usually caused by the surgery and pain medication. For symptomatic problems such as this, patients may, in some cases, be able to more accurately attribute the cause of an AE than their medical team.

To help patients live the best possible life with their condition, we ultimately need to look beyond clinical trial data toward new and emerging sources of information that highlight the real world, longitudinal experience of a broader and more diverse patient population.

The New Sources of Data

The idea of wellness goes well beyond simply taking a prescription. Patients who are actively monitoring and managing their health, documenting the side effects of their medications, making necessary adjustments, and sharing that information are a rich source of wellness insight for others. They are the key to helping all patients become better informed about the treatments they are taking and the health decisions they are making. In other words, they’re a great source for information about how to be well and stay well.

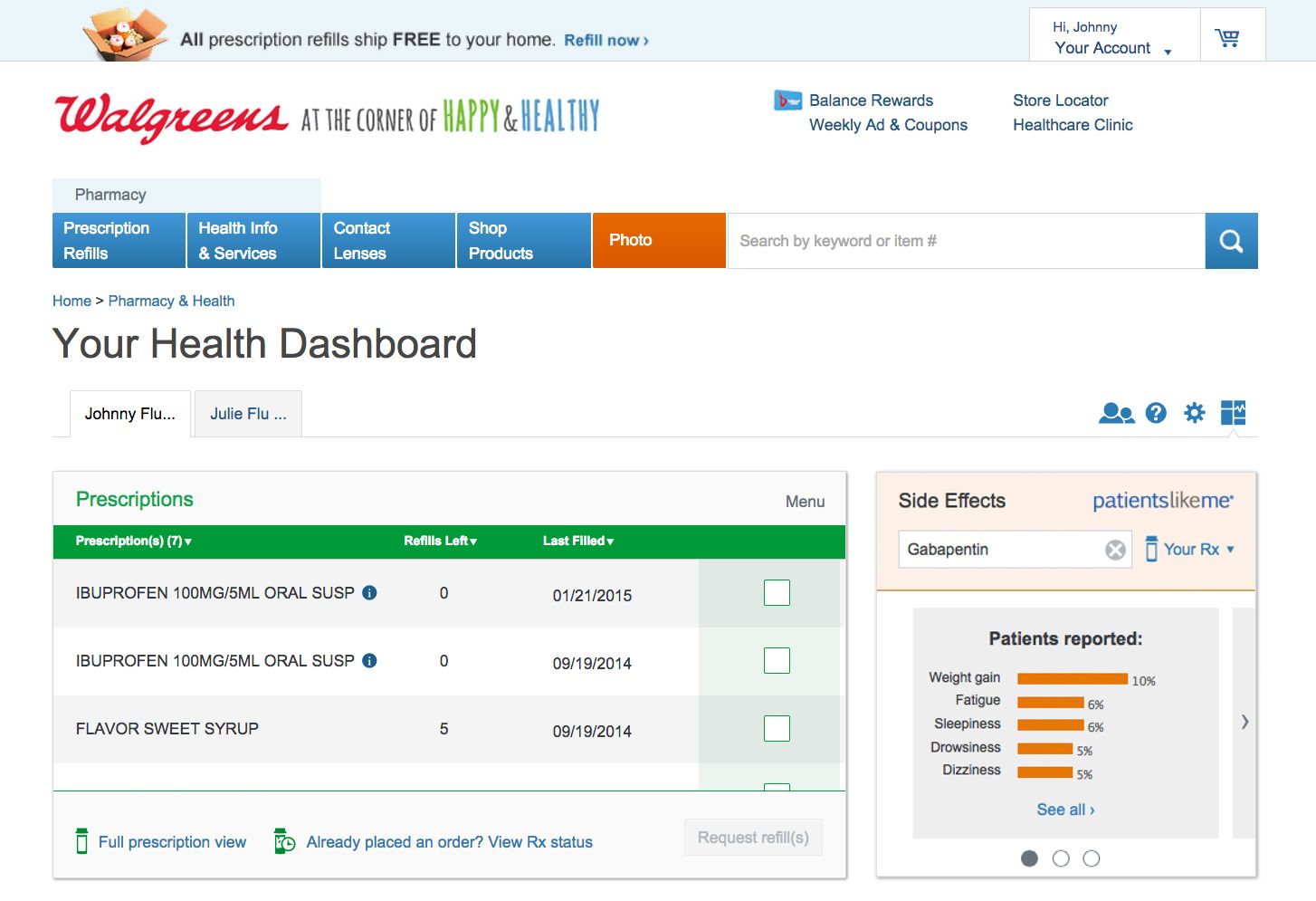

I work at PatientsLikeMe, where about 350,000 people have shared their experiences with various diseases and treatments. We recently partnered with Walgreens to share the side effect information we collect with their customers. Now, anyone researching a medication or filling a prescription on Walgreens.com can access a simple snapshot that shows how their prescribed medication has impacted affected other patients on the therapy, including medication side effects, as reported by PatientsLikeMe members. The data are updated daily with new patient reports and cover close to 6000 medications.

New technologies and methods for sharing health data encourage connected patients to be engaged in all aspects of wellness, including goal-setting, social support, and continuous learning. This learning, however, can go well beyond the virtual walls of a website. We’ve just begun to collaborate with the FDA to determine how patient-reported data can give new insights into drug safety. Our goal is to systematically explore the potential of patient-generated data to inform regulatory review activities related to risk assessment and risk management. Since the data on PatientsLikeMe are generated in a different context by the patients themselves, they provide important real-time insights into the nuances inherent in patients’ experiences over time, including drug tolerance, adherence, and QOL. Thus, the FDA will be able to see a real-world longitudinal profile of products and use a more current and innovative source of data to help identify product benefits and risks earlier.

Patients have actually been reporting drug safety information on our website since 2008. Back then, we started a pilot program that allowed patients living with multiple sclerosis to report AEs directly to the FDA. One year later, we launched the first drug safety platform on social media, enabling industry partners to meet their regulatory obligations. In all, we have collected more than 110,000 AE reports on 1000 different medications, data that the FDA will now be able to access and analyze as a supplement to traditional sources, including the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System.

Patients can contribute much more than their experience with medications. They are often a great source of information about how to live well with health problems and improve overall wellness. For example, injection site reactions such as pain, itching, or swelling are well-known side effects of most injectable medications. However, there is little information from clinical trials that can help patients manage these effects. Patients lessen the side effects by developing a variety of strategies such as massaging, heating, or cooling the injection site or rotating the injection site. Patients taking injectable medications that cause flu-like symptoms learn to schedule their administration on Friday so that their symptoms fall over the weekend and the impact on the rest of their lives is minimized.

Sharing information about side effects and living strategies can go a long way to improving wellness. Yet, some will object to this democratization of knowledge and patient-reported information. The reasons to ignore or question it are easy to identify; many feel that you can’t trust information from the Internet or anything that’s anecdotal. In addition, most of the patient-reported information on these sites has not been reviewed by a medical professional.

The reality is that patients are moving forward, with or without us. Not only can they report on their health, they are gaining access to and aggregating information from personal health records, medical devices, and wearables, all of which helps contribute to an understanding of how medications impact overall wellness far beyond established disease-specific clinical measures and assessments. More and more information will be generated as patients become more actively engaged in managing their health and well-being.

Clearly, our role as the keepers of drug/medical information is changing. Any drug information we have access to has been democratized online. Patients are becoming experts in their own care. It is our professional obligation to be aware of new types of information sources and consider how they can help patients. We drastically limit our impact as health professionals (not to mention our credibility) when we don’t adequately answer patients’ questions about the medication they are picking up. Patients are coming in with new ideas and solutions that you may not have any information about. We can’t just dismiss them because there aren’t peer-reviewed citations behind them. At the very least, the simple act of sharing information and getting feedback will create new opportunities for engaging patients in their health and behavior changes.

How can we better engage patients? We need to start by making sure we understand the larger goals they are trying to achieve. They may ask very simple questions when what they are really asking is essential to their wellness: what will this do to me, and how might it help me live with what I have? The FDA’s and Walgreens’ actions show that information generated by patients about their real-world experience will likely be the highest level of evidence that we have to be able to answer those questions in detail.

Knowing what patients might experience with a medication based on real-world insights will go a long way to strengthening patient—pharmacy relationships. Instead of bracing for their questions, you’ll be ready to share what you know when you hand over the bag and be better equipped to help patients achieve their ultimate wellness goals.

David Blaser, PharmD, is the director of health informatics at PatientsLikeMe, a patient network and real-time research platform. He designs and develops new ways of capturing, integrating, and understanding the medical information captured on the PatientsLikeMe platform. Dr. Blaser received his PharmD from Northeastern University in Boston and completed a fellowship in health outcomes and pharmacoeconomics at the University of Massachusetts Medical School. He continues to practice as a clinical pharmacist at Massachusetts General Hospital and is a member of the National Medical Device Registry Task Force.

References

- Radley DC, Finkelstein SN, Stafford RS. Off-label prescribing among office-based physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):1021-1026. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.9.1021.

- Carbidopa and levodopa: drug information. In: UpToDate [drug database]. Waltham, MA: UpToDate. Accessed September 12, 2015.

- Prograf (tacrolimus) [package insert]. Northbrook, IL: Astellas Pharma US, Inc; 2015.