Practice Pearl 1: Role of PARP Inhibitors in Ovarian Cancer

Sarah Hayward, PharmD, BCOP; Jennifer MacDonald, PharmD, BCOP; and Bradley J. Monk, MD, FACS, FACOG, discuss the relevance of PARP inhibition in the treatment of ovarian cancer and comment on the use of biomarker testing for treatment initiation.

Episodes in this series

Jennifer MacDonald, PharmD, BCOP: Hello. Good morning, good afternoon, or good evening, depending on when you might be viewing this Pharmacy Times® Practice Pearls program titled, “The Role of PARP Inhibitors in the Management of Ovarian Cancer.” My name is Jennifer MacDonald. I’m a gynecologic oncology specialist at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston, South Carolina. Joining me are 2 excellent speakers to lead our discussion with us. First, we have Dr Sarah Hayward, an oncology clinical pharmacy specialist in gynecologic oncology at Stephenson Cancer Center in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Also joining us is the esteemed Dr Bradley Monk, a professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of Arizona College of Medicine, and medical director at the US Oncology Research Network and Gynecologic Program, as well as vice president at the GOG Foundation in Phoenix, Arizona.

Bradley J. Monk, MD, FACS, FACOG: Thanks, Jen. It’s good seeing you. And hi, Sarah, it’s good seeing you, too. Thanks. I’m so excited.

Jennifer MacDonald, PharmD, BCOP: This is going to be a fun discussion. Today, we’re going to talk about topics pertaining to the use of PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer, with a focus primarily on these agents in the upfront maintenance setting. We’ll discuss how these have transformed the treatment paradigm for women facing ovarian cancer, the important distinctions between PARP inhibitors within this class to help guide selection of therapy, and the critical roles that pharmacists can play in the monitoring and management of PARP inhibitors in these patients.

With that, we’ll get started. First, we wanted to talk a little about how PARP inhibitors have a role in ovarian cancer. Sarah, given your clinical pharmacy expertise, what is the mechanism of these PARP inhibitors, and how is that particularly relevant to patients with ovarian cancer?

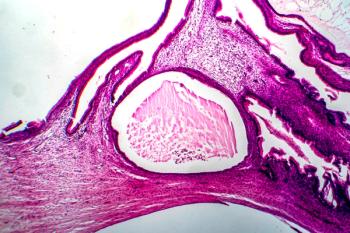

Sarah Hayward, PharmD, BCOP: Thanks for asking. The use of PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer has been a big paradigm shift in the treatment of this patient population. The majority of our patients with ovarian cancer have epithelial ovarian cancer and subtypes under that, especially high-grade serous. In that group, we have recognized that these patients have deficiencies in their repair mechanisms down to a molecular and DNA level. These are targetable deficiencies. This is where PARP comes into play. The PARP protein is one of the repair mechanisms that can help DNA repair itself, specifically those cancer cells. Our goal and the idea behind the mechanism is to block those PARP proteins so that the cells can’t repair, replicate, divide, and grow.

Jennifer MacDonald, PharmD, BCOP: Yes, that’s great. One of my very first things when I was a pharmacy resident was seeing the slide of double-stranded DNA breaks vs single-stranded DNA breaks, and I’ll always remember that picture. That has evolved, and Dr Monk could speak to that, too. We started with patients with BRCA mutations and it evolved into this whole homologous recombination deficient patient population, which has been pretty exciting.

Bradley J. Monk, MD, FACS, FACOG: By way of introduction, for those of you who are listening, PARP inhibitors aren’t just for ovarian cancer. We’ve got 4 tumor types: breast, pancreatic, prostate, and we’re going to focus on ovarian cancer. Basically, many of the indications are molecularly focused, so thank you, Sarah, for your nice answer. As Sarah just nicely said, what PARP does is it repairs single-stranded breaks. And if you inhibit that pharmacologically, an unrepaired single-stranded break becomes a double-stranded break.

The most important gene in repairing double-stranded breaks is BRCA. But it’s more than BRCA, it’s BRCA-like genes. And not just the mutations in those genes, but the epigenetic silencing. In fact, it’s the effect of those genes, the loss of heterozygosity, and the genomic scarring, which can be measured. That measure is called homologous recombination repair deficiency. Because double-stranded breaks are repaired by taking 1 chromosome as a template, lining it up to the broken sister chromatid, the homologue, and recombining it. And if you can’t homologously recombine, you’re deficient. You have HRD [homologous recombination deficiency]. That’s where the PARP inhibitors work.

Jennifer MacDonald, PharmD, BCOP: Yes. I love all of that science. We as pharmacists are all about all the mechanisms behind what we do. Dr Monk, when you meet a new patient with ovarian cancer who’s new to you, whether they’re newly diagnosed or are just a referral to you and have already been diagnosed, what kind of biomarker testing do you get for these patients to help guide whether you might be able to use one of these?

Bradley J. Monk, MD, FACS, FACOG: This has evolved. Every patient needs genetic counseling. The question is who’s going to do it. Our genetic counselors don’t want to tell a patient that every organization says you should get a BRCA test. That just isn’t very productive. So I tell them that, I counsel them, and I send a germline test on every patient. By ovarian cancer, I mean fallopian tube and peritoneal. And it’s not just the BRCA test, it’s all the germline genes associated with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. There are some laboratory tests where if there isn’t a germline BRCA, then you pivot to the tumor, and the tumor could have a somatic BRCA mutation or an HRD molecular signature. We do germline in everyone and somatic in every patient who doesn’t have a germline BRCA mutation.

Jennifer MacDonald, PharmD, BCOP: Perfect. We practice very similarly. Is that similar to you as well, Sarah?

Sarah Hayward, PharmD, BCOP: Yes, absolutely.

Jennifer MacDonald, PharmD, BCOP: Perfect. We do the same thing. I think we do both tests on everyone, regardless.

Bradley J. Monk, MD, FACS, FACOG: It’s OK.

Jennifer MacDonald, PharmD, BCOP: Yes, just in case we catch extra things for trials, like POLE or ARID1A, or whatever it might be, to catch that stuff. But yes, that’s great.

Bradley J. Monk, MD, FACS, FACOG: The good thing is that because this is a companion diagnostic, it’s paid for by CMS [Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services], and basically no patient gets a co-pay. I don’t want people out there saying, “I don’t want to do that because it’s too expensive.” That may be relevant to the European Union, but in the United States, it’s almost always universally paid for without a co-pay. Germline first, and if you want to do somatic at the same time, it’s OK.

Jennifer MacDonald, PharmD, BCOP: That’s great. Obviously, each institution has its own caveats with whether they refer that out.

Bradley J. Monk, MD, FACS, FACOG: Yes.

Jennifer MacDonald, PharmD, BCOP: Or they do it within the institution, or whatever it may be. A lot of that logistical stuff is, at least for us, a pathology issue and a little beyond us to some degree, but the physicians help with that.

Transcript Edited for Clarity

Newsletter

Stay informed on drug updates, treatment guidelines, and pharmacy practice trends—subscribe to Pharmacy Times for weekly clinical insights.