- September 2013 Oncology

- Volume 79

- Issue 9

Pneumococcal Disease: The Whole Story in 10 Points

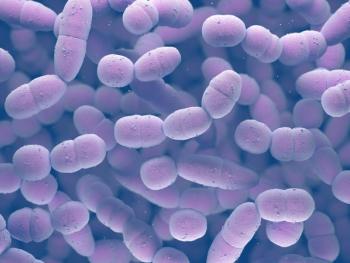

Streptococcus pneumoniae is the leading cause of life-threatening illness globally.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is the leading cause of life-threatening illness globally.

The gram-positive bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae (S pneumoniae or simply pneumococcus) was identified in 1886.1-3 It spreads via airborne droplets and is the leading cause of pneumonia and other life-threatening illnesses globally.4-6 Approximately 4 million Americans contract pneumococcal infections every year.7-9 The most serious infection, invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD), causes 400,000 to 500,000 hospitalizations annually and about 10% of patients die.6,10-14 This scourge is vaccine preventable to a great extent. This article explains pneumococcal disease in 10 points.

1. Pneumococcal disease infects our most vulnerable disproportionately (online Table 1). Furthermore, small children and the elderly are at greater risk of death if they develop IPD.5,6

Table 1: Populations at Risk for Pneumococcal Disease

Children:

· Younger than 2 years

· Who attend group child care

· Who have certain chronic or autoimmune illnesses

· With cochlear implants or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks

· Who are of American Indian, Alaska Native, and African American origin

Adults:

· Aged 65 years and older

· At any age who

· Have chronic heart, kidney liver, or lung disease; asthma; diabetes; or alcoholism

· Have autoimmune conditions

· Reside in long-term care facilities

· Have cochlear implants or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks

· Smoke

Source: Reference 15

2. Because of its changeable polysaccharide capsule, pneumococcus occurs as more than 90 known serotypes and 46 serogroups, all of which can cause otitis media (OM), sinusitis, and bronchitis. A few serotypes can enter blood, cerebrospinal, joint, pleural, or pericardial sites to cause IPD.10

3. Workers and war created pressure to find vaccines. The earliest interest in a pneumococcal vaccine occurred in South Africa in 1911. The country’s economy depended on gold mining. The labor force, much of which emigrated from distant rural areas, was prone to infections. Britain considered closing mines due to escalating morbidity and mortality from lobar pneumonia, prompting the mining industry to push for a vaccine.16-18 While researchers did not find a vaccine, they delineated the disease-causing pneumococcal serotypes and clarified the typical immune response.19,20

World War I’s flu pandemic created more pressure for a vaccine as soldiers and civilians—more than 70 million—died of flu complications. Pneumococcal pneumonia was also a problem during World War II. The barrier: pharmaceutical companies' financial challenges were high, and societal acceptance of vaccinations was low. When antibiotic resistance emerged in the 1970s, society became more receptive to the idea of a vaccine. The FDA approved a 14-valent vaccine in 1978.21

Even with the vaccine, the World Health Organization (WHO) tagged pneumococcal disease as a global problem. WHO assembled a multinational survey to determine which serotypes posed the greatest problem, then recommended moving to 23-valent vaccines. This simple proposal translated into an intimidating, costly challenge. Merck and Lederle independently introduced pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccines (PPV23) in 1983 that covered approximately 87% of pneumococcal diseases in the United States. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) immediately recommended vaccinating 2 high-risk groups: children older than 2 years who had certain underlying chronic medical conditions, and people older than 65 years.7,22

4. The earliest vaccines weren’t for little kids! Nonconjugated PPVs activate B cells but elicit T-cell independent immune responses. Children younger than 2 years cannot mount these protective responses. Additionally, PPVs do not induce immune memory, are devoid of booster effect, and have almost no effect on nasopharyngeal carriage in patients of any age.23 Researchers continued to search for vaccines for wide use in small children.

5. Today’s vaccines are effective in all age groups. The FDA licensed a 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) in 2000. PCV7 could be used in infants and young children. Safe and highly effective (~97%) against IPD, PCV7 was also moderately effective against pneumonia, and somewhat effective in reducing OM episodes and office visits.24-26 ACIP now recommends routine PCV7 use for children aged 2 to 59 months.14,27

The PCV7 vaccine’s routine use decreased rates of IPD caused by PCV7-covered serotypes by more than 90% over the next few years. Within a year, IPD caused by PCV7-covered serotypes had been completely eliminated in children younger than 5 years in the United States. Overall and over several years, the vaccine reduced preventable infection by 94% in all ages.28

Given the high burden of IPD caused by serotypes in PPV23 but not newer vaccines, patients who are immunocompromised or at elevated risk (online Table 2) still need the PPV23 vaccine. Additionally, clinical trials have not been conducted using the PCVs in these populations.

6. Pneumococcal disease is an intergenerational issue even though most children receive immunizations. Up to 50% of young children are colonized with S pneumoniae, and almost all children in day care are carriers. Before the PCV7 vaccine was available, statisticians identified an annual post-holiday spike of IPD in January among elderly people in January among elderly people—a spike attributed to family holiday gatherings.32,33 Adults who live with a day care—attending child 6 years or younger are at an increased risk of pneumococcal infection. HIV-infected adults who have contact with children are at elevated risk for IPD.32-35

Herd immunity is working. After children were routinely vaccinated with PCV7, the incidence of IPD caused by the 7 serotypes in the vaccine declined 92% in adults older than 65 years.32-35

Table 2: Serotype Coverage at a Glance

Serotypes

PPV23

PCV7

PCV13

1

+

+

2

+

3

+

+

4

+

+

+

5

+

+

6A

+

6B

+

+

+

7F

+

+

8

+

9N

+

9V

+

+

+

10A

+

11A

+

12F

+

14

+

+

+

15B

+

17F

+

18C

+

+

+

19A

+

+

19F

+

+

+

20

+

22F

+

23F

+

+

+

33F

+

Source: References 22, 29, 30, and 31

7. The picture of pneumococcal disease changes under pressure from vaccination. After PCV7 became available, the incidence of diseases caused by non-PCV7 serotypes (especially 6A, 15, and 19A) increased in children and at-risk adult populations. These increases were small compared with the overall reduction in disease.36-40 Regardless, PCV7’s coverage was imperfect.

In February 2010, the FDA approved a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13).31 In addition to the 7 serotypes included in PCV7, PCV13 has 6 more serotypes (1, 3, 5, 6A, 7F, and 9A). PCV13 is approved for prevention of IPD caused by the 13 serotypes in the vaccine among infants and young children. This product is labeled for OM prevention related to the 7 serotypes covered by PCV7 only. ACIP now recommends PCV13 for all children aged 2 months to 5 years and others at risk. In 2011, the FDA approved PCV13 for people 50 years and older to prevent pneumonia and IPD.31

8. Despite the availability of vaccines, IPD and influenza are the eighth-leading cause of death in the United States.41 Some experts blame serotype replacement, which has increased prevalence of serotypes already present in the population, or the appearance of new serotypes formerly unable to compete with more pathogenic serotypes to cause disease.42 Experts agree that serotype replacement, while disquieting, doesn’t outweigh vaccination’s benefits.43

9. Vaccination uptake rates among adults need improvement. Healthy People 2020 identifies a target vaccination rate of 90% for people 65 years and older,44 but only 30.5% of patients in high-risk groups have been vaccinated.45 Cost should not be a barrier, as Medicare covers this vaccine.

10. Influenza and pneumococcus coinfection is common during epidemics, causing about one-fourth of influenza-related deaths.46 The incidence of all-cause pneumonia is 29% less and mortality is 35% less in elders vaccinated against both influenza and pneumococcal disease. This also reduces and shortens hospitalizations.47 Let’s remind elders that they need both pneumococcal and influenza vaccinations.

Conclusion

Pharmacists in many states can vaccinate against pneumococcal disease. However, patients often refuse the vaccine for various reasons. A small number (>7%) belong to the anti-vaccine movement. Elders, feeling that they are approaching life’s end, simply abandon preventive care.48 The most important thing we can do is offer the vaccine and explain its importance.

Ms. Wick is a visiting professor at the University of Connecticut School of Pharmacy and a certified pharmacist immunizer.

References:

- Sternberg GM. A fatal form of septicaemia in the rabbit, produced by the subcutaneous injection of human saliva. Natl Board Health Bull. 1881;2:781-783.

- Pasteur L. Note sur la maladie nouvelle provoque´ par la salive d’un enfant mort de la rage. Bull Acad Me´d (Paris). 1881;10:94-103.

- Malkin HM. The trials and tribulations of George Miller Sternberg (1838—1915): America’s first bacteriologist. Perspect Biol Med. 1993;36:666-668.

- Nuorti JP, Whitney CG. Prevention of pneumococcal disease among infants and children: use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine—recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1-18.

- Thigpen MC, Whitney CG, Messonnier NE, et al. Bacterial meningitis in the United States, 1998-2007. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2016-2025.

- Active bacterial core surveillance (ABCS) report; emerging infections program network; Streptococcus pneumoniae [database online]. CDC website. www.cdc.gov/abcs/index.htm. Accessed August 29, 2013.

- CDC. Prevention of pneumococcal disease. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1997;46(RR-8):1-20.

- Block SL, Hedrick J, Harrison CJ, et al. Community-wide vaccination with the heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate significantly alters the microbiology of acute otitis media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:829-833.

- Casey JR, Pichichero ME. Changes in frequency and pathogens causing acute otitis media in 1995-2003. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:824-828.

- Huang SS, Johnson KM, Ray GT, et al. Healthcare utilization and cost of pneumococcal disease in the United States. Vaccine. 2011;29:3398-3412.

- Robinson KA, Baughman W, Rothrock G, et al. Epidemiology of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae infections in the United States, 1995-1998: opportunities for prevention in the conjugate vaccine era. JAMA. 2001;285:1729-1735.

- Dowell SF, Marcy SM, Phillips WR, Gerber MA, Schwartz B. Otitis media: principles of judicious use of antimicrobial agents. Pediatrics. 1998;101:165-171.

- Bogaert D, De Groot R, Hermans PW. Streptococcus pneumoniae colonisation: the key to pneumococcal disease. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:144-154.

- CDC. Preventing pneumococcal disease among infants and young children: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49(No. RR-9):1-35.

- CDC. Pneumococcal disease risk factors & transmission. www.cdc.gov/pneumococcal/about/risk-transmission.html. Accessed August 7, 2013.

- Wright AE, Morgan WP, Colebrook L, Dodgson RW. Observations on prophylactic inoculation against pneumococcus infections, and on the results which have been achieved by it. Lancet. 1914;10:87-95.

- Heffron R. Pneumonia with special reference to pneumococcal lobar pneumonia. New York, NY: Commonwealth Fund; 1939:446-483, 805-936, 946.

- Austrian R. Of gold and pneumococci: a history of pneumococcal vaccines in South Africa. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 1977;89:141-161.

- Austrian R. The development of pneumococcal vaccine. Proc Am Phil Soc. 1981;125:46-51.

- Kazanjian P. Changing interest among physicians toward pneumococcal vaccination throughout the twentieth century. J Hist Med Allied Sci. 2004;59:555-587.

- Grabenstein JD, Klugman KP. A century of pneumococcal vaccination research in humans. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(suppl 5):15-24.

- CDC. Updated recommendations for prevention of invasive pneumococcal disease among adults using the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1102-1106.

- Pitsiou GG, Kioumis IP. Pneumococcal vaccination in adults: does it really work? Respir Med. 2011;105:1776-1783.

- Black S, Shinefield H, Fireman B, et al. Efficacy, safety and immunogenicity of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children. Northern California Kaiser Permanente Vaccine Study Center Group. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:187-195.

- Black SB, Shinefield HR, Ling S, et al. Effectiveness of heptavalent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in children younger than five years of age for prevention of pneumonia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21:810-815.

- Eskola J, Kilpi T, Palmu A, et al. Efficacy of a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against acute otitis media. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:403-409.

- CDC. Updated recommendation from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) for use of 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) in children aged 24-59 months who are not completely vaccinated. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:343-344.

- O'Brien KL, Wolfson LJ, Watt JP, et al. Burden of disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet. 2009;374:893-902.

- Committee on Infectious Diseases; American Academy of Pediatrics. Pneumococcal infections. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Long SS, McMillan JA. Red Book 2009 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 28th ed. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009:525-535.

- CDC. Invasive pneumococcal disease in children 5 years after conjugate vaccine introduction: eight states, 1998-2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:144-148.

- CDC. Licensure of a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) and recommendations for use among children: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:258-261.

- Feikin DR, Klugman KP, Facklam RR, Zell ER, Schuchat A, Whitney CG. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance/Emerging Infections Program Network. Increased prevalence of pediatric pneumococcal serotypes in elderly adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:481-487.

- Walter ND, Taylor TH Jr, Dowell SF, Mathis S, Moore MR. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance System Team. Holiday spikes in pneumococcal disease among older adults. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2584-2585.

- Wroe PC, Lee GM, Finkelstein JA, et al. Pneumococcal carriage and antibiotic resistance in young children before 13-valent conjugate vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31:249-254.

- Henderson FW, Gilligan PH, Wait K, Goff DA. Nasopharyngeal carriage of antibiotic-resistant pneumococci by children in group day care. J Infect Dis. 1988;157:256-263.

- CDC. Direct and indirect effects of routine vaccination of children with 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on incidence of invasive pneumococcal disease: United States, 1998-2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:893-897.

- Flannery B, Heffernan RT, Harrison LH, et al. Changes in invasive pneumococcal disease among HIV-infected adults living in the era of childhood pneumococcal immunization. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:1-9.

- Byington CL, Hulten KG, Ampofo K, et al. Molecular epidemiology of pediatric pneumococcal empyema from 2001 to 2007 in Utah. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:520-525.

- Muñoz-Almagro C, Jordan I, Gene A, Latorre C, Garcia-Garcia JJ, Pallares R. Emergence of invasive pneumococcal disease caused by nonvaccine serotypes in the era of 7-valent conjugate vaccine. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:174-182.

- Aaberge I. Experience with pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in Norway. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2009;8:159-165.

- Heron M, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: leading causes for 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2009;58:1-97.

- Lipsitch M. Bacterial vaccines and serotype replacement: lessons from Haemophilus influenzae and prospects for Streptococcus pneumoniae. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:336-345.

- Hanage WP, Finkelstein JA, Huang SS, et al. Evidence that pneumococcal serotype replacement in Massachusetts following conjugate vaccination is now complete. Epidemics. 2010;2:80-84.

- Chang YC, Chou YJ, Liu JY, Yeh TF, Huang N. Additive benefits of pneumococcal and influenza vaccines among elderly persons aged 75 years or older in Taiwan: a representative population-based comparative study. J Infect. 2012;65:231-238.

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. Healthy people 2020: national health promotion and disease prevention objectives. www.healthypeople.gov. Accessed December 14, 2012.

- Dear K, Holden J, Andrews R, Tatham D. Vaccines for preventing pneumococcal infection in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;4:CD000422.

- Jefferson T, Rivetti D, Rivetti A, Rudin M, Di Pietrantonj C, Demicheli V. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines in elderly people: a systematic review. Lancet. 2005;366:1165-1174.

- Assaad U, El-Masri I, Porhomayon J, El-Solh AA. Pneumonia immunization in older adults: review of vaccine effectiveness and strategies. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:453-461.

Articles in this issue

over 12 years ago

Can You Read These Rxs?over 12 years ago

Case Studiesover 12 years ago

Glaucoma Treatment in Nursing Home Often Combined with Other Medsover 12 years ago

Leading the Way to Improved Careover 12 years ago

Pet Peevesover 12 years ago

Your Compounding Questions Answeredover 12 years ago

NCCN Guidelines May Improve Ovarian Cancer Outcomesover 12 years ago

Regular Exercise Linked to Reduced Ovarian Cancer Riskover 12 years ago

Men Favor Prostate Cancer Test Despite Task Force RecommendationNewsletter

Stay informed on drug updates, treatment guidelines, and pharmacy practice trends—subscribe to Pharmacy Times for weekly clinical insights.