- June 2020

- Volume 88

- Issue 6

Let’s Be Ready to Test and Vaccinate

No matter how it all shakes out, pharmacists now have a level of responsibility they never had before.

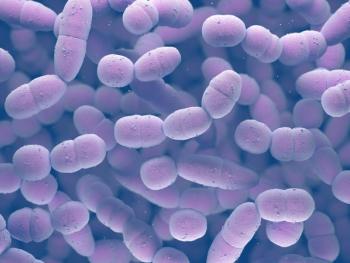

With an incubation period of 2 to 14 days1 and up to a third of infected individuals never having symptoms but likely contagious, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) seems like the perfect biological vehicle to create an uncertain health care system and widespread social unrest.

Although we have no long-term data on this virus or the disease it causes, COVID-19 seemingly spares most children and young adults.

Yet simple math also tells us that COVID- 19 has been catastrophic for others, wiping out wide swaths of residents in long-term care facilities with exceptionally high fatality rates under heart-wrenching circumstances. Some of these victims have not been able to see their loved ones before their deaths, and others have been entirely forgotten without family to even notice. This virus kills some groups with frightening speed and remains inconsequential and invisible to other groups. So, what should we do if we find that the main vehicles of COVID-19 transmission are not the affected but the unaffected?

ASYMPTOMATIC, DANGER TO OTHERS

Common sense and conventional wisdom would point to a natural feedback loop wherein those without immunity take precautions to avoid sickness and death to themselves. Yet, with high numbers of asymptomatic cases and mortality rates relatively low among young adults (0.06% for 20- to 24-year-olds vs 13.4% in individuals 80 years and older, a 223-times greater risk for the latter), the perception of vulnerability to COVID-19 for the young is low to most anyone who is not an epidemiologist.2 This false sense of security may cause a 21-year-old who rarely gets sick to scoff at wearing a mask at the grocery store and spread the virus just as efficiently as those who feel sick.

The results of a study published in April suggest that individuals infected with COVID-19 are most contagious 1 to 3 days before demonstrating any symptoms, with 44% of transmissions occurring from patients during asymptomatic or presymptomatic infection.3 This finding highlights the devilish nature of this virus: Full containment requires restriction of movement for massive numbers of people who may or may not have an active infection.

REVISITING H1N1 TO BETTER UNDERSTAND SOCIETAL DIVIDES ABOUT RESPONDING TO COVID-19

The 2009 H1N1 outbreak killed far fewer Americans (12,469) than COVID-19 has.4 But unlike COVID-19, the healthy and young were particularly susceptible. That difference in risk by age changes our collective feelings about risk tradeoff, whether we like to admit it or not.

An article written that year by Michael Osterholm, MD, at the University of Minnesota Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy in Minneapolis, put it this way, “The way we count influenza mortality and influenza-related death in an 87-year-old person with advanced Alzheimer disease is the same as the death of a 22-yearold otherwise perfectly healthy pregnant woman. Both deaths are equally tragic, but any reasonable person would agree they are not equivalent public health outcomes.”

He then went on to discuss the concept of years of potential lives lost and lists percentages of death due to H1N1 by age category: children 0 to 17 years (11%); those aged 18 to 64 years (76%), and people 65 years and older (13%).5 Imagine how much differently we would have responded to COVID-19 if the relative rates of death by age matched H1N1. We would have nearly 100,000 working-aged adults and about 10,000 children dead as of the beginning of June 2020, and nobody would be arguing much against stay-at-home efforts.

COVID-19 DEATHS BY AGE EERILY SIMILAR TO OTHER CAUSES

The COVID-19 pandemic produces a near mirror image to the 2009 H1N1 outbreak by age category and a very similar distribution of death by age compared with influenza and all other causes of disease, according to an analysis of data from New York City, in which 0.23% of the entire population had died from COVID-19 as of early May 2020. Those 65 years and older in the US made up 80% of all COVID-19 deaths versus 78% of all “internal” causes of death.6 The elderly and sick have been more likely to die from COVID-19 than the well and young. It is not complicated, right?

YET THE HEALTHY AND YOUNG STILL FACE GREATER RISK

But relativity can be deceiving. Against other age groups and with mitigation, death rates from COVID-19 are low for the young. Against influenza, and with mitigation, rates of death from COVID- 19 can be about the same. But if COVID-19 is left unchecked and without an effective treatment or vaccine, rates of death can rise at least 10-fold against influenza for young adults.6 The unmitigated spread of COVID-19 could kill many middle-aged people, too.

EMOTIONS ARE RUNNING HIGH, UNDERSTANDABLY

Tradeoffs are difficult when applied to whole populations. Each of us tolerate different degrees of reward and risk. Generation Xers and millennials made up 68% of our workforce as of 2017,7 and up until now, have borne a relatively (there’s that word again) low burden of death but have experienced a high burden of economic pain. It is plausible that unemployment rates resulting from COVID-19 mitigation efforts will exceed 30% among the members of these generations. Child abuse, domestic violence, heart attacks, substance abuse, and suicides are likely increasing because of COVID-19 mitigation efforts. There are no easy answers on how to deal with the hand that nature has dealt us.

ROLE OF TESTING REMAINS UNCERTAIN

In an ideal world, we would have ready access to a test that produces a perfect negative and positive predictive value with the social goodwill and supplies to test everyone at once. We would determine who needs to be quarantined for a couple of weeks, pay them for lost wages, and dramatically reduce the spread of COVID-19 to near nothing. Yet, this is not our reality.

Anyone who is tested using nasopharyngeal swabs the day they get infected will have a false-negative rate of 100% because of a lack of enough antigen built up to produce a finding, according to the Harvard Coronavirus Resource Center.8

After 4 days, that false sense of security only drops to 40%, and even after 3 days of exhibiting symptoms of COVID-19, the false-negative rate remains at 20%.8 Saliva testing may offer some modest improvement.

KEY QUESTION

Osterholm often asks, “What’s our goal?” in public forums. If we cannot answer that, we will not know how to proceed without accessible and reliable testing, or even if we should proceed. We are using antigen testing as a confirmatory diagnostic for those with symptoms with limited accessibility and are appropriately not using it to rule out COVID-19. We have some antibody tests available to determine if an individual has responded to a COVID- 19 infection by producing immunoglobulin G and immunoglobulin M antibodies with varying degrees of predictive value, but how do we interpret findings if we do not know the necessary level of antibodies to produce near immunity? We are all waiting for reliable testing.

Reliable testing could be our greatest asset to identify and trace outbreaks. Reliable testing could give many people the confidence to get back to the work site, sing at church, or socialize at the salon. Reliable testing could identify COVID-19 early in the disease progression and save lives if early treatment is found to be essential. Reliable testing could allow grandparents to know when they can safely play with their grandchildren.

PHARMACIES AND PHARMACISTS AT THE READY

Engineers and scientists will eventually provide reliable testing solutions, and epidemiologists, politicians, and public health officials are likely to answer the question of testing goals. Our goals should focus on the provision of care: providing an unbiased ear for patient concerns, reasonable actions to mitigate against spread at the pharmacy, and preparation for mass testing, public education, and vaccination.

Because of this pandemic, the US Department of Health and Human Services has provided pharmacists with a level of responsibility never conferred before. We can order a test. We can do the testing. We can vaccinate. We can be compensated. Let’s be ready.

Troy Trygstad, PharmD, PhD, MBA, is vice president of pharmacy programs for Community Care of North Carolina, which works collaboratively with more than 1800 medical practices to serve more than 1.6 million Medicaid, Medicare, commercially insured, and uninsured patients. He received his PharmD and MBA degrees from Drake University and a PhD in pharmaceutical outcomes and policy from the University of North Carolina. He also serves on the board of directors for the American Pharmacists Association Foundation and the Pharmacy Quality Alliance.

REFERENCES

- Clinical questions about COVID-19: questions and answers. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated May 12, 2020. Accessed May 27, 2020. cdc.gov/ coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/faq.html

- Ruan S. Likelihood of survival of coronavirus disease 2019. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(6):630-631. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30257-7

- He X, Lau EHY, Wu P, et al. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):672-675. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5

- 2009 H1N1 pandemic (H1N1pdm09 virus). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated June 11, 2019. Accessed May 27, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/ pandemic-resources/2009-h1n1-pandemic.html

- Osterholm MT. Making sense of the H1N1 pandemic: what’s going on? University of Minnesota Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy. December 14, 2019. Accessed May 27, 2020. https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/news-perspective/2009/12/making- sense-h1n1-pandemic-whats-going

- Fox J. Coronavirus deaths by age: how it’s like (and not like) other disease. Bloomberg. May 7, 2020. Accessed May 27, 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/ articles/2020-05-07/comparing-coronavirus-deaths-by-age-with-flu-driving-fatalities

- Fry R. Millennials are the largest generation in the U.S. labor force. Pew Research Center. April 11, 2018. Accessed May 27, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/facttank/ 2018/04/11/millennials-largest-generation-us-labor-force/

- Coronavirus research center. Harvard Health Publishing. Updated May 22, 2020. Accessed May 27, 2020. https://www. health.harvard.edu/diseases-and-conditions/ coronavirus-resource-center

Articles in this issue

over 5 years ago

Flatirons Family Is Not Your Traditional Pharmacyover 5 years ago

Caplyta From Intra-Cellular Therapies, Incover 5 years ago

Women With Autoimmune Thyroid Disease Have Higher Risk of PCOSover 5 years ago

New Regulations Aim to Reform Self-Referral Stark Lawover 5 years ago

Middle-Aged Women Often Develop Hypertensionover 5 years ago

OTC Case Studies: Women's Healthover 5 years ago

Toxicity Is a Risk of PAMORA Interactionsover 5 years ago

Pharmacy Schools Are Important for MTM Servicesover 5 years ago

Hypothyroidism Is Associated With Lower Risk in Breast CancerNewsletter

Stay informed on drug updates, treatment guidelines, and pharmacy practice trends—subscribe to Pharmacy Times for weekly clinical insights.