Pharmacy Practice in Focus: Health Systems

- March 2019

- Volume 8

- Issue 2

Here Is What to Know About Vaccines for Seniors

Being knowledgeable about the guidelines and risk factors for patients is important to ensure that they get the proper counseling on immunizations.

Aging is associated with an increase in the risk and severity of infectious diseases. Because of immunosenescence, the weakening of the immune system and progressive decline of adaptive and innate immune responses as we age, illnesses can cause significant mortality and morbidity in elderly persons.1,2 Immunosenescence is also responsible for the reduced efficacy of vaccines in older adults and is why older populations are more susceptible to the flu,

As a group, acute respiratory infections, including

Whether in the clinic, community, or hospital, a pharmacist can be very influential in following the CDC’s recommended immunization practices to administer and document immunizations, educate on the importance of

Specific Vaccines

Influenza

Influenza leads to more than 36,000 deaths and 200,000 hospitalizations each year, and more than 90% of influenza-related deaths reported annually occur in patients 65 and older. The CDC recommends that adults >50 years receive 1 dose of inactivated influenza vaccine or a recombinant influenza vaccine annually.5

The influenza vaccine should be offered by the end of October each year, and vaccination should optimally occur before the onset of influenza activity in the community.5 The effectiveness of influenza vaccines declines relative to age; because, of this, several new high-dose influenza vaccines have been developed.

The high-dose influenza vaccine Fluzone, an egg-based vaccine, is designed specifically for those >65 years and contains 4 times the amount of antigen as the regular flu vaccine. Results from a clinical trial of more than 30,000 participants showed that those >65 years who received the high-dose vaccine had 24% fewer influenza infections compared with those who received the standard dose.5,6 Flublok is another recombinant vaccine with 3 times the amount of antigen of standard vaccines.5,7

FLUAD is an acceptable alternative for those >65 years. Adjuvants are added to FLUAD to enhance the immune response.

No head-to-head trials of these vaccines have been undertaken.5

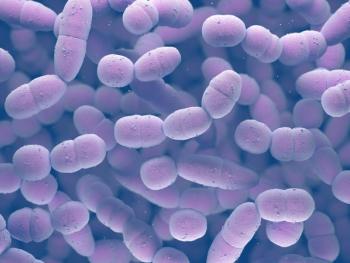

Pneumococcal

The incidence and mortality rate of pneumococcal disease tend to increase after age 50, and these increases are more often seen after age 65.8 The vaccine regimen for individuals older than 65 years involves 2 vaccines: the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23), Pneumovax, and the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), Prevnar.9

PPSV23 is less immunogenic but covers 10 more strains than PCV13. PCV13 is more immunogenic with better immunologic memory. Because each vaccine offers additive advantages, the CDC includes both in its recommended schedule.

The recommended interval between PCV13 and PPSV23 is ≥1 year for immunocompetent adults aged ≥65.9 However, for those with immunocompromising or special conditions, the recommended time to wait is ≥8 weeks. The ACIP also recommends that all adults aged ≥65 who received PPSV23 should receive a dose of PCV13 ≥1 year later.9

For immunocompetent adults who received PPSV23 before age 65 years and for whom an additional dose of PPSV23 is indicated when ≥65 years, this subsequent PPSV23 dose should be given ≥1 year after PCV13 and ≥5 years after the most recent dose of PPSV23.9

Herpes Zoster

Herpes zoster results from reactivation of the varicella zoster virus, which remains latent in the sensory ganglia following primary infection. The lifetime risk of developing herpes zoster is estimated at 20% to 30% of the general population and up to 50% among those living to at least age 85. Forty percent of those older than 60 who have had herpes zoster suffer from chronic neuropathic pain. Age is the main risk factor, and both the risk and severity increase after age 50.

There are 2 vaccines for shingles prevention in the United States. Zostavax is a 1-dose live attenuated zoster vaccine approved in 2005 for immunocompetent adults aged >50 and is recommended by the ACIP for use in immunocompetent adults >60 years. In individuals aged 60 and older, Zostavax has an efficacy rate of 51% in protecting against herpes zoster and reduces the occurrence of postherpetic neuralgia by 66.5%.10

In 2017, Shingrix, an adjuvanted herpes zoster subunit vaccine, was approved. Shingrix is indicated for the prevention of herpes zoster in adults >50 years and requires 2 doses, administered 2 to 6 months apart for full effectiveness.11

In separate clinical trials, estimates of Shingrix’s efficacy against herpes zoster were higher than Zostavax vaccine estimates in all age categories. The difference in efficacy between the 2 vaccines was most pronounced among those ≥70 years. Study results show that the effectiveness of the Zostavax vaccine wanes substantially over time, resulting in reduced protection against herpes zoster. Shingrix elicited similar safety and immunogenicity profiles, regardless of prior Zostavax vaccine receipt, and so revaccination with Shingrix will likely be beneficial.

Other Vaccines and Special Populations

Tetanus is caused by the bacterium Clostridium tetani. It is a relatively uncommon infection, but contamination of wounds in unvaccinated people can result in disease characterized by muscular spasms and sometimes death.

Adults who have never received a dose of acellular pertussis vaccine, reduced diphtheria toxoid, or tetanus toxoid, should receive a 1-time dose of the tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis vaccine as an adult, followed by a tetanus and diphtheria toxoids booster every 10 years.

Some elderly people may require vaccinations for hepatitis A; hepatitis B; measles, mumps, and rubella; meningococcal disease; and varicella, because of the health problems, occupations, or risks posed by their lifestyles. If such older adults travel, it is advisable to offer relevant vaccines.

Adults with immunosuppression should avoid live vaccines. Inactivated vaccines (eg, pneumococcal vaccines) are generally acceptable. Other immunocompromising conditions and immunosuppressive medications to consider when vaccinating adults can be found in the Infectious Diseases Society of America’s guidelines.12

Barriers to Immunizations

Despite recommendations, vaccination rates among adults continue to be low. In the United States, just 63% of older adults were immunized against the flu during the 2014-2016 season, only 61.3% of Americans 65 and older were immunized against pneumococcal pneumonia, and the herpes zoster vaccine had the lowest adult immunization rate at 27.9%.

The Healthy People 2020 initiative was formed with the goals of identifying nationwide public health opportunities, which include encouraging vaccination and increasing awareness about preventable diseases. Goals in this initiative include a 90% vaccination rate of influenza and pneumococcal vaccines in adults 65 and older and a 30% vaccination rate among adults 60 and older.13

Barriers to immunizations include fear of immunization pain, misconceptions and miseducation, and lack of access or insurance.

The Pharmacist's Role

For elderly patients, pharmacists are often the most accessible health care providers. Being knowledgeable about the guidelines and risk factors for patients is important to ensure that they get the proper counseling on vaccines.

The scope of pharmacist-administered vaccine administration varies from state to state, but in most states, a pharmacist is able to assess and administer at least the influenza and pneumococcal vaccines. If a state limits administering other vaccines, pharmacists can still educate and recommend them to their health care providers for further evaluation.

Joanna Lewis, PharmD, MBA, has worked in a variety of practice settings, most recently as a coordinator at Duke University Hospital in Durham, North Carolina.

References

- Weng NP. Aging of the immune system: how much can the adaptive immune system adapt? Immunity. 2006;24(5): 495-499.

- Esposito S, Franco E, Gavazzi G, et al. The public health value of vaccination for seniors in Europe. Vaccine. 2018;36(19):2523-2528. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.03.053.

- Ozawa S, Portnoy A, Getaneh H, et al. Modeling the economic burden of adult vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(11):2124-2132.

- CDC. General best practice guidelines for immunization course. cdc.gov/vaccines/ed/general-recs/index.html. Updated February 22, 2018. Accessed February 25, 2019.

- CDC. Influenza ACIP vaccine recommendations. cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/vacc-specific/flu.html. Updated September 5, 2018. Accessed January 25, 2019.

- Gravenstein S, Davidson HE, Taljaard M, et al. Comparative effectiveness of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccination on numbers of US nursing home residents admitted to hospital: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(9):738-746. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30235-7.

- Dunkle LM, Izikson R, Patriarca P, et al. Efficacy of recombinant influenza vaccine in adults 50 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(25): 2427-2436. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1608862.

- CDC. Active bacterial core surveillance (ABCs). cdc.gov/abcs/reports-findings/surv-reports.html. Updated July 17, 2018. Accessed January 29, 2019.

- CDC. Pneumococcal vaccine timing for adults. cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/pneumo/downloads/pneumo-vaccine-timing.pdf. Updated November 30, 2015. Accessed January 25, 2019.

- Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, et al. A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(22): 2271-2284.

- CDC. Shingles (herpes zoster). cdc.gov/shingles/vaccination.html. Updated January 25, 2018. Accessed January 27, 2019.

- Rubin LG, Levin MJ, Ljungman P, et al. 2013 IDSA clinical practice guidelines for vaccination of the immunocompromised host. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(3):e44-100. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit684.

- US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. Immunization and infectious diseases. HealthyPeople.gov website. healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/immunization-and-infectious-diseases. Updated February 21, 2019. Accessed February 25, 2019.

Articles in this issue

almost 7 years ago

Use AUC to Optimize Vancomycin Dosingalmost 7 years ago

Approach Respiratory Illnesses Rationallyalmost 7 years ago

Manage Acute Pain in Those Using Opioidsalmost 7 years ago

Documenting 340B Value Is Key to Successalmost 7 years ago

Panelists Discuss Challenges of Diagnosing HEalmost 7 years ago

News and Trends March 2019almost 7 years ago

Perform an AOR to Comply With USPalmost 7 years ago

Enterprise Collaborations Help Meet Challengesalmost 7 years ago

Cancer Pain Treatment Remains a Challengealmost 7 years ago

RA Treatment Strategies Can Keep the Pain at BayNewsletter

Stay informed on drug updates, treatment guidelines, and pharmacy practice trends—subscribe to Pharmacy Times for weekly clinical insights.