- Immunization Guide for Pharmacists

- Volume 1

- Issue 4

New Vaccines in the Pipeline 2019

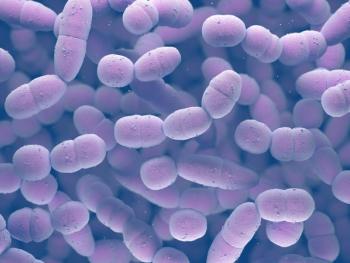

According to the World Health Organization, 240 vaccines were in development for 25 infectious diseases.5 Topping the list for most candidate vac- cines are HIV/AIDS, malaria, pneumococcal infec- tions, tuberculosis, and Ebola.

Before clinicians can administer a vaccine in the United States, the FDA must approve and license it. Investigators conduct extensive research leading up to this process, typically testing a vaccine in thousands of patients over 6 to 7 years or longer.1 Even with large sample sizes and rigorous study designs, rare adverse effects may be missed. For example, RotaShield, the first vaccine for rotavirus, was withdrawn from the market in 1999, despite being tested in more than 10,000 patients. Postmarketing surveillance demonstrated that a rare, yet serious, risk of intussusception was linked to the vaccine, and the FDA determined that the vaccine’s risks outweighed its benefits.2

Once the FDA approves a vaccine, the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) can make a recommendation for its use. Although the FDA focuses on the safety and efficacy of the vaccine, the ACIP can consider more aspects, such as the epidemiology of the disease, health economic impact, and implementation challenges, when making its recommendation.3 In addition, the US Department of Defense advocates for expedited development, review, and emergency use authorization of medical products that may benefit the US military forces or the general public.4

According to the World Health Organization, 240 vaccines were in development for 25 infectious diseases.5 Topping the list for most candidate vaccines are HIV/AIDS, malaria, pneumococcal infections, tuberculosis, and Ebola.

Vaccines of interest in development include those for the following conditions listed in the table.6-19

New Delivery Systems

Combination vaccines are advantageous because they mitigate the burden of multiple injections, reduce the number of visits, and save on costs for storage and shipment.20 In 2018, the FDA approved a new hexavalent vaccine, DTaP5-HB-IPV- Hib (Vaxelis, Merck) for primary and booster vaccination in infants and toddlers against diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, hepatitis B, poliomyelitis, and invasive disease caused by Haemophilus influenzae type b.21,22

Vaccine adjuvants are important for eliciting desired protective and sustained immune responses against target pathogens.23 In recent years, investigators have studied many novel adjuvants for clinical development, such as the oil-in-water emulsion MF59, which is currently being used in Fluad, an influenza vaccine, as well as ASO1B (eg, Shingrix, GSK) and CpG 1018 (eg, Heplisav-B, Dynavax).

Novel Vaccines

Vaccine technology has also been applied to the treatment of noninfectious disease conditions and areas such as cancer,24 smoking cessation,25 and hypertension.26 Vaccines that target tumor-associated antigens have been shown to prolong the survival of patients with metastatic melanoma with minimal toxicity.27 An angiotensin II vaccine is also in development for hypertension.26

CONCLUSION

The challenges that investigators face while developing a vaccine are unique, from infectious diseases that mutate at varying rates to efforts to develop a safe vaccine that not only targets the correct strain but also elicits an adequate immunologic response. Although this article has discussed a handful of vaccines in the pipeline, investigators are evaluating many others on a global scale. Despite the obstacles for vaccine development, FDA vaccine approvals have accelerated over the past 2 decades, making the prevention of even more human diseases in the future a realizable prospect (figure).28

Michael Phan, PharmD, is an assistant research professor, Chapman University School of Pharmacy, Irvine, California.Luma Munjy, PharmD, is an assistant professor of pharmacy practice, Chapman University School of Pharmacy, Irvine, California.

Nicole Benipayo, BS, is a student pharmacist, Chapman University School of Pharmacy, Irvine, California.Jeff Goad, PharmD, MPH, is a professor in and chair of the Department of Pharmacy Practice, Chapman University School of Pharmacy, Irvine, California.Sun Yang, PhD, BSPharm, is an assistant professor of pharmacy practice, Chapman University School of Pharmacy, Irvine, California.

REFERENCES

- Ensuring the safety of vaccines in the United States. FDA website. fda.gov/media/83528/download. Updated July 2011. Accessed May 31, 2019.

- Schwartz JL. The first rotavirus vaccine and the politics of acceptable risk. Milbank Q. 2012;90(2):278-310. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00664.x.

- The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and the childhood immunization schedule. CDC website. cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/conversations/downloads/vacsafe-acip-color-office.pdf. Updated January 2018. Accessed May 31, 2019.

- Horowitz D, Druckman M. FDA and DoD strengthen collaboration for medical products with military applications that could also be expanded to the general population. Hogan Lovells website. hlregulation.com/2018/11/08/fda-dod-strengthen-collaboration-medical-products-military-applications. Published November 8, 2018. Accessed May 31, 2019.

- Health products in the pipeline for infectious diseases. WHO website. who.int/research-observatory/monitoring/processes/health_products/en/. Published September 2018. Accessed May 31, 2019.

- About dengue: what you need to know. CDC website. cdc.gov/dengue/index.html. Updated May 3, 2019. Accessed May 31, 2019.

- First FDA-approved vaccine for the prevention of dengue disease in endemic regions [news release]. Silver Spring, MD: FDA; May 1, 2019. fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/first-fda-approved-vaccine-prevention-dengue-disease-endemic-regions. Accessed May 31, 2019.

- Questions and answers on dengue vaccines. World Health Organization website. who.int/immunization/research/development/dengue_q_and_a/en. Updated April 20, 2018. Accessed May 31, 2019.

- Rotavirus: questions and answers. Information about the disease and vaccines. Immunize Action Coalition website. immunize.org/catg.d/p4217.pdf. Accessed May 31, 2019.

- Bines JE, At Thobari J, Satria CD, et al. Human neonatal rotavirus vaccine (RV3-BB) to target rotavirus from birth. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(8):719-730. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706804.

- About HIV/AIDS. CDC website. cdc.gov/hiv/basics/whatishiv.html. Updated April 24, 2019. Accessed May 31, 2019.

- Global HIV & AIDS statistics—2018 fact sheet. UNAIDS website. unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet. Accessed May 31, 2019.

- Developing a vaccine against HIV infection. Avert website. avert.org/professionals/hiv-science/developing-vaccine. Reviewed April 4, 2019. Accessed May 31, 2019.

- Gray GE, Laher F, Lazarus E, Ensoli B, Corey L. Approaches to preventative and therapeutic HIV vaccines. Curr Opin Virol. 2016;17:104-109. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.02.010.

- Robb ML, Rerks-Ngarm S, Nitayaphan S, et al. Risk behaviour and time as covariates for efficacy of the HIV vaccine regimen ALVAC-HIV (vCP1521) and AIDSVAX B/E: a post-hoc analysis of the Thai phase 3 efficacy trial RV 144. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(7):531-537. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70088-9.

- Bekker LG, Moodie Z, Grunenberg N, et al; HVTN 100 Protocol Team. Subtype C ALVAC-HIV and bivalent subtype C gp120/MF59 HIV-1 vaccine in low-risk, HIV-uninfected, South African adults: a phase 1/2 trial. Lancet HIV. 2018;5(7):e366-e378. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(18)30071-7.

- Tuberculosis (TB): data and statistics. CDC website. cdc.gov/tb/statistics/default.htm. Updated December 31, 2018. Accessed May 31, 2019.

- Tuberculosis vaccine development. Word Health Organization website. who.int/immunization/research/development/tuberculosis/en/. Updated May 16, 2019. Accessed May 31, 2019.

- Pfizer announces presentation of data from a phase 2 study of its 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine candidate being investigated for the prevention of invasive disease and pneumonia in adults aged 18 years and older [news release]. New York, NY: Pfizer; April 13, 2019. pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/pfizer_announces_presentation_of_data_from_a_phase_2_ study_of_its_20_valent_pneumococcal_conjugate_vaccine_candidate_being_ investigated_for_the_prevention_of_invasive_disease_and_pneumonia_in_ adults_aged_18_years. Accessed May 31, 2019.

- Obando-Pacheco P, Rivero-Calle I, Gómez-Rial J, Rodríguez-Tenreiro Sánchez C, Martinón-Torres F. New perspectives for hexavalent vaccines. Vaccine. 2018;36(36):5485-5494. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.06.063.

- Xu J, Stek JE, Ziani E, Liu GF, Lee AW. Integrated safety profile of a new approved, fully liquid DTaP5-HB-IPV-Hib vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2019;38(4):439-443. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002257.

- Syed YY. DTaP5-HB-IPV-Hib vaccine (Vaxelis): a review of its use in primary and booster vaccination. Paediatr Drugs. 2017;19(1):69-80. doi: 10.1007/s40272-016-0208-y.

- Mbow ML, De Gregorio E, Valiante NM, Rappuoli R. New adjuvants for human vaccines. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22(3):411-416. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.04.004.

- Ozao-Choy J, Lee DJ, Faries MB. Melanoma vaccines: mixed past, promising future. Surg Clin North Am. 2014;94(5):1017-1030. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2014.07.005.

- Goniewicz ML, Delijewski M. Nicotine vaccines to treat tobacco dependence. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(1):13-25. doi: 10.4161/hv.22060.

- Nakagami H, Morishita R. Therapeutic vaccines for hypertension: a new option for clinical practice. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2018;20(3):22. doi: 10.1007/s11906-018-0820-z.

- Dillman RO, Cornforth AN, Nistor GI, McClay EF, Amatruda TT, Depriest C. Randomized phase II trial of autologous dendritic cell vaccines versus autologous tumor cell vaccines in metastatic melanoma: 5-year follow up and additional analyses. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0330-1.

- Vaccine timeline. Immunize Action Coalition website. immunize.org/timeline/. Updated February 13, 2019. Accessed May 31, 2019.

Articles in this issue

over 6 years ago

Empowering Patients to Know Their Immunization Historyover 6 years ago

Immunizing Patients Is Worth Pharmacists' and Technicians' Timeover 6 years ago

Healthy People 2020: Immunization Goalsover 6 years ago

Tackling Vaccination Hesitancy Unrelated to Medical Exemptionover 6 years ago

Addressing Immunizations in Pregnant and Lactating Womenover 6 years ago

Hepatitis B Virus: Who Is at Risk, and What Can We Do?Newsletter

Stay informed on drug updates, treatment guidelines, and pharmacy practice trends—subscribe to Pharmacy Times for weekly clinical insights.