- August 2019 Back to School

- Volume 85

- Issue 8

How Often Do Patients Need Meningococcal Vaccines?

Meningitis is a deadly condition that affects up to 1 million people per year globally.1

Meningitis is a deadly condition that affects up to 1 million people per year globally.1 It is characterized by inflammation of the meninges but can also affect the parenchyma (meningoencephalitis), the spinal cord, and the ventricles (ventriculitis).2 The most common and lethal meningitis is bacterial, but several types exist: amebic, fungal, noninfectious, parasitic, and viral.1,3

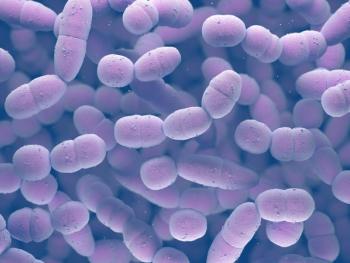

The rate of meningococcal disease is at a low in the United States, declining since the 1990s.4 Since the inception of the meningococcal conjugate vaccine recommendation, the rate of meningococcal disease caused by serogroups C, Y, and W has decreased by 80% among 11-to-19-year-olds.4 Importantly, remember that meningitis is not synonymous with meningococcal disease.3 Meningococcal disease is any illness caused by Neisseria meningitidis, but bacterial meningitis in the United States is often caused by group B Streptococcus, Haemophilus influenzae, Listeria monocytogenes, Neisseria meningitidis, and Streptococcus pneumoniae.5 Bacterial meningitis is a medical emergency, and fortunately, vaccinations are available and recommended to prevent the disease.

The bacterium that causes meningococcal disease, N meningitidis, has 5 serogroups, A, B, C, W, and Y, that are covered under 2 types of vaccinations4: conjugate vaccines (Menactra and Menveo) and serogroup B (recombinant) vaccines (Bexsero and Trumenba).

INFANTS AND CHILDREN

The meningococcal vaccination is not routinely recommended for all infants and young children but is recommended in special circumstances. The CDC recommends that infants and children aged 2 months

to 10 years receive the meningococcal conjugate vaccines (Menactra and Menveo) if any of the following special conditions are present4: complement component deficiency, damaged spleen or asplenia, HIV, residing or traveling near a meningococcal disease outbreak, taking Soliris, or traveling to places where meningitis is common.

Children who continue to have an increased risk of contracting meningococcal disease should receive their booster shot 3 years after their first vaccination.6

The CDC recommends the serogroup B menin- gococcal vaccine for children 10 years or older if any of the following special conditions are met4: at increased risk because of a serogroup B meningococcal disease outbreak, complement component deficiency, damaged spleen or asplenia, or taking Soliris.

PRETEENS AND TEENS

This age group is at increased risk of contracting meningitis.7 Therefore, the vaccination is routine. The CDC recommends that all children aged 11 to 12 years receive their first dose of meningococcal vaccine followed by a booster shot at age 16.4 Between ages 16 and 18, all teenagers can also get the serogroup B meningococcal vaccine, and the CDC recommends it especially for preteens and teens if they are taking Soliris, have asplenia or spleen damage, have complement component deficiency, or plan to travel to places at increased risk of meningococcal outbreak.4

ADULTS

The CDC does not recommend the meningococcal vaccine routinely for adults, but the agency does recommend it for those in special circumstances.4 These include an adult who is a microbiologist who has a damaged spleen or asplenia; has complement component deficiency; has HIV; has increased risk because of a serogroup A, C, W, or Y meningococcal disease outbreak; is regularly exposed to N meningitidis; is in the military; is not up-to-date with this vaccine and is a first-year college student living in a residence hall; is taking Soliris; or is traveling to countries where the disease is common.

Patients should also get a serogroup B meningococcal vaccine if they4 are a microbiologist who is regularly exposed to N meningitidis, are at increased risk because of a serogroup B meningococcal disease outbreak, are taking Soliris, have a damaged spleen or asplenia, or have complement component deficiency.

FREQUENCY FOR SPECIAL CONDITIONS

The following populations should receive a booster of meningococcal ACWY (MenACWY) every 5 years: microbiologists who work with meningococcus, people with HIV infection, those who travel repeatedly to regions of Africa hyperendemic to meningococcal disease, and those without a spleen.8

Patients without a spleen are at increased risk of infections and should receive 2 doses of MenACWY separated by 8 weeks, then a booster dose every 5 years. They should also complete a series of meningococcal B vaccine, 2 or 3 doses, depending on the brand.7

Booster shots are not routinely recommended for meningococcal B disease.

MENINGITIS RISK WITH INTERNATIONAL TRAVEL

Meningitis and meningococcal disease occur around the world, but meningitis is more prevalent in certain countries. Specifically, the highest incidence of meningococcal disease occurs in sub-Saharan Africa, also known as the meningitis belt.9 Additionally, people who travel to Saudi Arabia for hajj or umrah are required to have proof of the quadrivalent (serogroup A, C, W, or Y) vaccination.9 Patients must receive the conjugate vaccines (MCV-4), Menactra and Menveo, no more than 8 years before arrival.9

CONTRAINDICATIONS

Patients with a history of allergic reaction to the MenACWY and meningococcal B vaccines themselves or ingredients in the vaccines should avoid them. Those who are moderately to severely ill should also avoid them.4

Sara Hunt, MSN, RN, PHN, FNP-C, is a licensed and board-certified family nurse practitioner, a public health nurse, an adjunct assistant professor of health policy, and a doctor of nursing practice student at the University of California, San Francisco. She was the spring 2015 health policy fellow at the American Association of Nurse Practitioners' Government Affairs Office in Washington, DC.

References

- Facts about meningitis. Confederate of Meningitis Organisations website. comomeningitis.org/facts-about-meningitis/. Accessed June 21, 2019.

- Hoffman O, Weber RJ. Pathophysiology and treatment of bacterial meningitis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2009;2(6):1-7. doi: 10.1177/1756285609337975.

- Meningitis. CDC website. cdc.gov/meningitis/index.html. Updated March 13, 2019. Accessed June 21, 2019.

- Meningococcal vaccination: what everyone should know. CDC website. cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/mening/public/index.html. Updated May 17, 2017. Accessed June 21, 2019.

- Bacterial meningitis. CDC website. cdc.gov/meningitis/bacterial.html. Updated January 25, 2017. Accessed June 21, 2019.

- Meningococcal: questions and answers. Immunization Action Coalition website. immunize.org/catg.d/p4210.pdf. Accessed June 21, 2019.

- Meningococcal vaccination for preteens and teens: information for parents. CDC website. cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/mening/public/adolescent-vaccine.html. Updated May 19, 2017. Accessed June 21, 2019.

- Vaccinations for adults without a spleen. Immunization Action Coalition website. immunize.org/catg.d/p4047.pdf. Accessed June 21, 2019.

- Meningococcal disease. CDC website. wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2018/infectious-diseases-related-to-travel/meningococcal-disease#5227. Updated June 12, 2017. Accessed June 21, 2019.

Articles in this issue

over 6 years ago

A Hospital and Physician Share Liability for Prescribing Opioidsover 6 years ago

Motivational Interviewing Offers a Path to Improved Adherenceover 6 years ago

Drug Shortages Raise Critical Safety Concernsover 6 years ago

Case Study: Albuterolover 6 years ago

340B Specialists Help Maintain Program Integrityover 6 years ago

How Can Patients Prevent and Treat Fall Allergies?over 6 years ago

Case Study: Vitamins for Eye HealthNewsletter

Stay informed on drug updates, treatment guidelines, and pharmacy practice trends—subscribe to Pharmacy Times for weekly clinical insights.