- May 2012 Skin & Eye Health

- Volume 78

- Issue 5

The Pain of Shingles: Symptoms May Persist After the Rash Heals

Long after the rash heals, the painful symptoms of shingles may persist for some patients.

Long after the rash heals, the painful symptoms of shingles may persist for some patients.

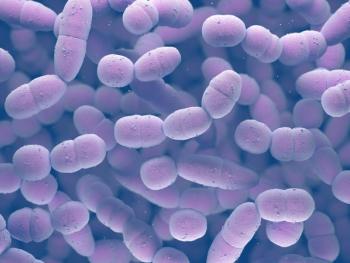

Herpes zoster—commonly called shingles—results from the reactivation of the varicella- zoster virus (VZV), which lies dormant in the spinal and cranial sensory ganglia following a primary infection with varicella (chicken pox), often during childhood.1 In chicken pox infection, VZV is highly contagious, and transmission occurs by direct contact with skin lesions or by respiratory aerosols from infected individuals.2 Reactivation usually occurs later in life when cell-mediated immunity declines or in patients with immune disorders.

VZV affects any level of the neuraxis, but common sites are the chest, face, and eye.2 Up to 90% of Americans are susceptible and approximately 33% of Americans develop shingles in their lifetime, resulting in 1 million episodes annually.3,4

Stages of Shingles

Disease progression occurs in 3 stages. The first, or prodromal, phase is characterized by symptoms of headache, pain, malaise, and photophobia. The second, or acute, phase is characterized by a dermatomal rash, often accompanied by unbearable itching, pain, and allodynia (site pain in response to innocuous stimuli such as clothing or wind). The rash typically lasts 7 to 10 days, with the majority of patients healing within 4 weeks.

The third phase, which is not experienced by all patients, is marked by complications such as postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) and eye involvement (herpes zoster ophthalmicus).3 Up to 20% of patients with shingles experience PHN, a chronic, debilitating, painful condition lasting months or years. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus, which affects up to 25% of patients, potentially results in pain, disfigurement, scarring, and vision loss.4

Along with these complications, research demonstrates that stroke risk is increased by 30% following a herpes zoster attack and is increased 4-fold if the attack involved the eye (the risk is higher for ischemic stroke than hemorrhagic stroke). Additionally, patients with VZV are more likely to have comorbidities, including hypertension, coronary artery disease, diabetes, heart failure, and renal disease.5

Treatment Options

Treatment objectives for the acute phase are symptom control and prevention of complications. Acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir are nucleoside analogues that inhibit replication of the herpes virus. When taken orally, these agents reduce the duration of viral shedding, promote rash healing, reduce the severity and duration of acute pain, and reduce PHN risk.6 Although acyclovir is the least expensive agent, famciclovir and valacyclovir are often the agents of choice because of their more favorable pharmacokinetic profiles and simpler dosing regimens.7

Antivirals are most effective when given within 72 hours of rash onset, although prompt recognition and treatment occur in less than 50% of cases.8 Additionally, oral corticosteroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or opioids may be required for pain management.8 Treatment with both antivirals and analgesics is essential in patients with ophthalmic zoster.2 Topical lidocaine patches are helpful for patients with allodynia.6

Managing PHN

PHN is defined as pain persisting more than 3 months following rash healing. Clinical features differ among patients, and range from constant pain characterized by burning, aching, or throbbing to intermittent pain characterized by stabbing or shooting pain. Additionally, some patients present with allodynia.9

PHN responds poorly to treatment.7 Optimal pain management is difficult to achieve, but one meta-analysis established analgesic efficacy for several orally administered agents including tricyclic antidepressants, opioids including tramadol, and anticonvulsants (gabapentin and pregabalin). Tricyclic antidepressants and gabapentin are first-line agents.9 Combination treatment with morphine and gabapentin decreases pain more than either agent administered alone.2

Preventing Shingles

A live attenuated viral vaccine became available in 1995. Research demonstrates that the vaccine is both safe and well tolerated; injection site reactions, however, are common (48%).1,10 The vaccine is contraindicated in those with bone marrow or lymphatic cancers, HIV/AIDS, and impaired humoural immunity.

Additionally, the vaccine is not recommended if patients are being treated with corticosteroids, methotrexate, azathioprine, mercaptopurine, or tumor necrosis factor inhibitors.1 Treatment with acyclovir, famciclovir, and valacyclovir may interfere with the vaccine.11 Patients taking these agents need to discontinue antivirals at least 24 hours prior to vaccination and must wait a minimum of 14 days before restarting antiviral treatment.1 The vaccine does not contain thimerosal or other preservatives and can be given with other vaccines.4

Although vaccination does not guarantee 100% prevention, the Shingles Prevention Study demonstrated the vaccine reduced zoster risk by 51.3%, reduced illness burden by 61.1%, reduced PHN risk by 66.5%, and reduced PHN by 39%.11 The duration of protection remains unknown, but data suggest protection persists up to 7 years. The need for revaccination has not been established.1

Counseling Points

When patients ask about an OTC product for a rash, probe for VZV symptoms, especially if the patient is elderly. At times, VZV may be the first symptom of a serious life-threatening immune disorder (eg, AIDS); encourage patients to see their physician. When patients present with a confirmed diagnosis, review adverse effects of antivirals, because up to 38% will experience at least 1 side effect.8

Inform patients that pain may persist after the rash heals, emphasizing that PHN requires treatment. When opioids are prescribed, recommend prophylactic constipation therapy, especially stool softeners and laxatives. Because clinical depression is associated with PHN, query for symptoms and encourage patients to seek treatment, noting that depression can be treated.6

Inform patients about the natural progression of herpes zoster and its potential complications. During the acute phase, patients are infective to others and should be instructed to avoid contact with elderly people, people who are immunocompromised, pregnant women, and people with no history of chicken pox infection. Instruct patients not to scratch the lesions, which will increase the risk for secondary bacterial infections.12

Because patients on corticosteroids have a high risk for developing VZV,3 they should be counseled regarding VZV’s prodromal symptoms, including allodynia, and directed to seek treatment within 72 hours of symptom onset.

Final Thought

Up to 50% of those 80 years and older will develop herpes zoster. Fewer than 15% of eligible adults are vaccinated, however.13 Pharmacists, along with all health professionals, must strive to change this statistic.

Agent

Recommend Dose

Comments

Acyclovir

800 mg 5 times a day for 7 to 10 days

-Bioavailability is 10% to 30%, necessitating frequent dosing. Adherence may be problematic for elders.

-Phlebitis or inflammation is a common adverse effect. Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and headache were reported in 2% to 3% of patients.

-Elevated creatinine may occur.

-IV acyclovir is indicated for patients who are immunocompromised.

Famciclovir

500 mg 3 times per day, but 250 mg 3 times a day may be equally effective

-Bioavailability is 77%.

-Equally effective as acyclovir.

-Up to 38% of patients report at least 1 adverse effect (headaches, nausea, or gastrointestinal disturbances (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and flatulence).

Valacyclovir

1 g 3 times a day for 7 days

-Bioavailability is 54.4%.

-Side effects are similar to famciclovir.

-Compared with acyclovir, valacyclovir is superior for accelerating pain reduction.

-Patients with renal disease must be monitored; hemolytic uremic syndrome is an uncommon but serious side effect.

IV = intravenous. Adapted from references 8, 12, 15, and 16.

Dr. Zanni is a psychologist and health-systems consultant based in Alexandria, Virginia.

References

1. Shapiro M, Kvern B, Watson P, Guenther L, McElhaney J, McGeer A. Update on herpes zoster vaccination: a family practitioner’s guide. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:1127-1131.

2. Mueller NH, Gilden DH, Cohrs RJ, Mahalingam R, Nagel MA. Varicella zoster virus infection: clinical features, molecular pathogenesis of disease, and latency. Neurol Clin. 2008;26:675-697, viii.

3. Weaver BA. Herpes zoster overview: natural history and incidence. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2009;109(6)(suppl 2):S2-S6.

4. Harpaz R, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Seward JF; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of herpes zoster: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57(RR-5):1-30.

5. Kang JH, Ho JD, Chen YH, Lin HC. Increased risk of stroke after a herpes zoster attack: a population-based follow-up study. Stroke. 2009;40:3443-3448.

6. Sampathkumar P, Drage LA, Martin DP. Herpes zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:274-280.

7. Cunningham AL, Breuer J, Dwyer DE, et al. The prevention and management of herpes zoster. Med J Aust. 2008;188:171-176.

8. Galluzzi KE. Managing herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2009;109(6)(suppl 2):S7-S12.

9. Johnson RW, McElhaney J. Postherpetic neuralgia in the elderly. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:1386-1391.

10. Galea SA, Sweet A, Beninger P, et al. The safety profile of varicella vaccine: a 10-year review. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(suppl 2):S165-S169.

11. Medscape Medical News. Guidelines issued on prevention of herpes zoster. www.medscape.org/viewarticle/574697. Accessed February 29, 2012.

12. Moon J. Herpes zoster. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/218683-overview. Accessed March 16, 2012.

13. Oxman M. Herpes zoster: who is at risk? www.medscape.org/viewarticle/755880. Accessed February 29, 2012.

14. Drolet M, Brisson M, Schmader KE, et al. The impact of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia on health-related quality of life: a prospective study. CMAJ. 2010;182:1731-1736.

15. Eastern J. Herpes zoster. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1132465-overview. Accessed March 16, 2012.

16. Thomson Reuters Healthcare Micromedex. Version number 1.29.0b1115.

Articles in this issue

over 13 years ago

Management of Cold Sores by Prescriptionover 13 years ago

Pet Peevesover 13 years ago

Case Studiesover 13 years ago

Can You Read These Rxs?over 13 years ago

Danger Lurks with Used Transdermal Patchesover 13 years ago

Intertwining MTM and Work Flowover 13 years ago

News & Trendsover 13 years ago

A Check-up Visit to the Pharmacy Can Save the Dayover 13 years ago

Health App Wrapover 13 years ago

Dermatologic Emergencies: Rapid Response by the PharmacistNewsletter

Stay informed on drug updates, treatment guidelines, and pharmacy practice trends—subscribe to Pharmacy Times for weekly clinical insights.