- January 2019 Vaccine-Preventable Disease

- Volume 85

- Issue 1

Learn How to Counter Vaccine Hesitancy

The most effective interventions in patients are multifaceted, not singly focused.

Immunizations have led to a significant decrease in rates of vaccine-preventable diseases and have had a positive impact on the health of children.

However, some parents express concerns about vaccine necessity and safety, leading to hesitancy about

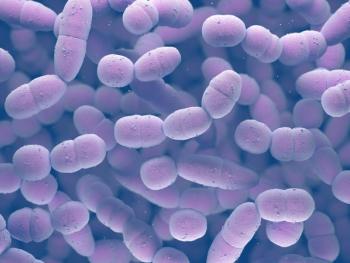

Take, for example, diphtheria, which was a major cause of death and illness among children in the era before immunization. There were 206,000 recorded cases of diphtheria in the United States in 1921, before immunization was available, resulting in 15,520 deaths.1 A vaccination became available in the later 1920s, and instances of diphtheria have declined since, with just 2 recorded cases in the United States between 2004 and 2015.1

Other examples include the elimination of polio and smallpox from the United States.2,3 Elimination of a disease means that there is no year-round transmission. However, sometimes a traveler will bring a disease into the United States from another country.

According to the CDC, vaccine-preventable diseases have declined dramatically from the prevaccine eras. In addition to the instances of the diseases listed above, cases of hepatitis A, measles, mumps, pertussis, rubella, tetanus, and varicella have decreased by more than 90%. Instances of other diseases have decreased by 70% to 89%.4

Vaccination has been one of the most successful public health interventions in the world.5 It is estimated that vaccines save 6 million to 9 million lives each year and prevent 95% of childhood diseases.5 Because the associated bacteria and viruses still exist, vaccine rates must remain high enough to prevent these diseases from proliferating.

Inform hesitant parents and patients that vaccination of a sufficiently high percentage of the population grants broad community protection.5 This is called herd immunity, and it is based on varying rates of immunization per vaccine. In general, herd immunity develops at an immunization rate of 80% to 95%.5 Herd immunity is essential for protecting the health of individuals who cannot be vaccinated, those who are especially susceptible to communicable diseases, and those who choose not to vaccinate.5

By age 2, children are required to have 16 to 20 doses of vaccines, yet 20% of children in the United States are deficient in 1 or more recommended immunizations.6 Several reasons exist for these low immunization rates. When determining these causes, clinicians should be aware that there may be many interrelated factors.

Some of the causes are detailed here.

COMMUNICATION AND MEDIA

In his 2011 book The Panic Virus: A True Story of Medicine, Science, and Fear, journalist Seth Mnookin described how vaccination has become a topic of fear and fodder for misinformation. He also described how the media keep vaccine scares alive, even in the face of robust evidence of the effectiveness and safety of vaccines.7

PUBLIC HEALTH AND VACCINE POLICIES

In recent years, there has been an increase in the number of new vaccines commercialized and licensed on the market. This increase has led to differing opinions about whether these vaccines should be incorporated into the regular vaccine schedule or used to create new schedules. These differing opinions may be fueling the negative perception of particular vaccines or vaccine schedules.8

The reliability and strength of vaccine safety surveillance are often not fully understood by the population and even some health care providers. Inaccurate information concerning vaccine safety as well as the process leading to vaccine licensure circulates extensively.8

HEALTH CARE PROFESSIONALS

The interaction between patients and providers is important in maintaining trust in vaccination. Generally, health care providers are strong supporters of vaccines. However, some health care providers can be considered vaccine hesitant.8

MISINFORMATION

Lack of knowledge on the “who, what, and when” related to vaccination can contribute to vaccine hesitancy. Also, relying on inaccurate data, overthinking, and placing too much emphasis on other people’s opinions can reduce vaccination rates.

PAST EXPERIENCES

Accessibility to and the convenience of vaccinations are an important part of determining vaccine uptake. The quality of vaccination services may also influence vaccine uptake. Past negative experiences may reduce vaccine rates as well.

RISK PERCEPTIONS

The 2 dimensions typically used to assess risk perceptions are the perceived likelihood of harm and the perceived severity of the consequences if harm were to occur.8 These risks are balanced against the perceived benefits and cost of an action to prevent this harm.8

ALTERNATIVE AND COMPLEMENTARY MEDICATIONS

Association between the use of complementary and alternative medicine is inversely proportional to vaccine uptake.8

LACK OF TRUST

An important predictor of acceptance of a vaccine is the recommendation from a health care professional. Vaccination decisions are closely related to trust in health professionals, the government, and public health institutions, as well as the interplay among all 3. Trust is based not only on knowledge but also on faith that health professionals know best based on familiarity.8

SOCIAL PRESSURE AND RESPONSIBILITY

Viewing vaccination as a social norm is a powerful driver of vaccine uptake. The perception that members of a social circle, whom individuals respect and trust, are receiving vaccinations makes others more likely to follow suit. Social responsibility, specifically the recognition of vaccination as an individual duty to maintain herd immunity, can also increase vaccine acceptance.

MORAL AND RELIGIOUS CONVICTIONS

Vaccine refusal has been linked to moral convictions and philosophical beliefs, such as the preference of natural over artificial medicines. In addition, several religions oppose vaccination in part because the idea is not in keeping with the need for preventive action, the search for a cure, or the views of the origins of illness.8

SOLUTIONS

Unfortunately, there is no single strategy that will address all vaccine hesitancy. The most effective interventions are multifaceted, not singly focused.9 To better identify factors influencing vaccine hesitancy, the World Health Organization has developed The Guide to Tailoring Immunization Programmes.9 It includes proven methods and tools to diagnose vaccine-preventable disease in susceptible populations, identifies supply-and-demand barriers and enablers, and recommends evidence-based responses to build and sustain vaccination rates.9 The pharmacist is a knowledgeable agent who can help dispel false claims about vaccines and address vaccine hesitancy on a case-by-case basis. Because pharmacists are one of the most accessible health care professionals in the United States, patients often seek knowledge from them and trust that they are fair, honest, and impartial health care providers with patients’ best interests at heart.

Kathleen Kenny, PharmD, RPh, has more than 25 years of experience as a community pharmacist and is a freelance clinical medical writer based in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

REFERENCES

- Vaccines work! Immunization Action Coalition website. immunize.org/catg.d/ p4037.pdf. Accessed July 29, 2018.

- Lee EO, Rosenthal L, Scheffler G; Center for American Progress. The effect of childhood vaccine exemptions on disease outbreaks. cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/ uploads/2013/10/VaccinesBrief-1.pdf. Published November 14, 2013. Accessed October 23, 2018.

- Diphtheria: clinicians. CDC website. cdc.gov/diphtheria/clinicians.html. Updated January 16, 2016. Accessed July 29, 2018.

- Polio elimination in the United States. CDC website. cdc.gov/polio/us/index.html. Updated November 28, 2017. Accessed July 29, 2018.

- Smallpox: clinical disease. CDC website. cdc.gov/smallpox/clinicians/clinicaldisease.html. Updated December 5, 2016. Accessed July 29, 2018.

- Low immunization rates. CDC website. cdc.gov/healthcommunication/ toolstemplates/entertainmented/tips/LowImmRates.html. Updated February 15, 2011. Accessed July 28, 2018.

- Mnookin S. The Panic Virus: A True Story of Medicine, Science, and Fear. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 2011.

- Dubé E, Laberge C, Guay M, Bramadat P, Roy R, Bettinger J. Vaccine hesitancy: an overview. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(8):1763-1773. doi: 10.4161/hv.24657.

- Addressing vaccine hesitancy. World Health Organization website. who. int/immunization/programmes_systems/vaccine_hesitancy/en/. Updated September 21, 2018. Accessed July 28, 2018.

Articles in this issue

about 7 years ago

Organize Marketing to Increase Pharmacy Cash Flowabout 7 years ago

Can Pharmacists Take Legal Action After Being Fired?about 7 years ago

New Opioid Approval Creates Controversyabout 7 years ago

Patients Are Increasingly at Risk for Insulin-Drug Interactionsabout 7 years ago

Managing Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Poses Challengesabout 7 years ago

Pharmacists Need to Understand Law Related to Controlled Substancesabout 7 years ago

Minimize the Likelihood of Vaccine-Related Adverse ReactionsNewsletter

Stay informed on drug updates, treatment guidelines, and pharmacy practice trends—subscribe to Pharmacy Times for weekly clinical insights.