Publication

Article

Pharmacy Times

Is This the Year of Regulatory Change and Special Legislation? (Part 2)

Potential actions related to the opioid epidemic and pharmacist provider status are on the horizon.

In Part 1 of "Is This the Year of Regulatory Change and Special Legislation?", I wrote about pharmacy benefit managers as well as the larger supply chain of the pharmaceutical industry being on the hot seat as spread pricing and the industry’s reliance on rebates seem to have started the process of unravelling, at least politically. Tangentially tied to those hotbed issues are “provider status,” as pharmacists do some soul-searching about sustainable financing models, and the opioid epidemic as it continues to infect and tear apart communities without abatement.

Provider Status: What is it?

Pharmacists from all tribes of pharmacy (and now pharmacies that need an alternative payment model) are more aggressively seeking out provider status as an existing means of salary support and sustainable revenue for product reimbursement (in both community and health systems pharmacies) becomes more at risk. But what is provider status?

One of the timeless traditions in pharmacy is ambiguity when describing what we do or want to do every day at work (see medication therapy management and the like). What exactly, do these terms mean? They often mean different things to different people, holding different perspectives and different models of professional sustainability. This is not easy to solve, so I do not blame the progenitors or supporters of the terms. But it is important to acknowledge, because all of us in pharmacy need all of us to thrive for any 1 group to thrive.

THE TRIUMVIRATE OF PROVIDER STATUS

Scope of practice. This relates to what pharmacists are allowed to do and direct with respect to the delivery of health care services. Emerging examples are administration of long-acting injectables, initiating and performing point-of care-testing, prescriptive authority related to scheduled drugs, and any other number of activities performed by a pharmacist that are codified generally into medical practice and/or state pharmacy acts.

Scope of recognition. This relates to the mechanical machinations of our health care system as well as cultural and societal phenomena. On the mechanical side, an example would be the National Provider Identifier. On the societal side, we still see physician television dramas in prime time, providing role models for aspiring students but await pharmacist dramas to emerge. Clearly, we are not there yet, but it is important to understand that societal recognition matters. The American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy recently acknowledged as much by devoting significant resources to help improve societal awareness of the role and importance of pharmacists in our health care system through its Pharmacists for Healthier Lives campaign (pharmacistsforhealthierlives).1

Scope of work and payment. This is what concerns most millennial pharmacists as they worry about out how to support a family and pay student loans off over the next 30 to 40years. It is what most pharmacists now think of when they hear “provider status.” Interestingly, a pharmacist can sign a scope of work and get paid for services without changes in scope of practice and recognition. It is generally a battle with accountants and budget directors, not boards of medicine. Scopes of work are contracts with payers or other purchasers of services, such as patients using health savings accounts or a public health department buying health coaches and diabetes prevention specialists.

STEADY AS SHE GOES

It is important to understand these variations in the context of provider status when following legislative, political, or regulatory activity. You may read that “provider status is achieved” in this state or that state or “please donate to our political action committee so we can achieve federal provider status,” and those 2 efforts have different effects on the day-to-day and future practice and work.

Regardless of which context, my belief is that we want and need all hands on deck in all corners of pharmacy supporting local, national, and state pharmacist associations, colleges, companies, guilds, societies, or any other way we associate in advancing “provider status” and payment transformation away from product reimbursement and toward sustainable services for the collective benefit. Here is a shout-out to the efforts of California, Idaho, Ohio, Washington, and a bunch of other states efforts, as well as the American Pharmacists Association and its counterparts at the national level to continue to build the effort, piece by hard-fought-for piece.

Look for accelerated activity on these fronts in 2019 and beyond as the cultural and economic necessity of payment transformation for pharmacists begins to come to a head.

OPIOIDS CONTINUE TO RESONATE WITH MANY

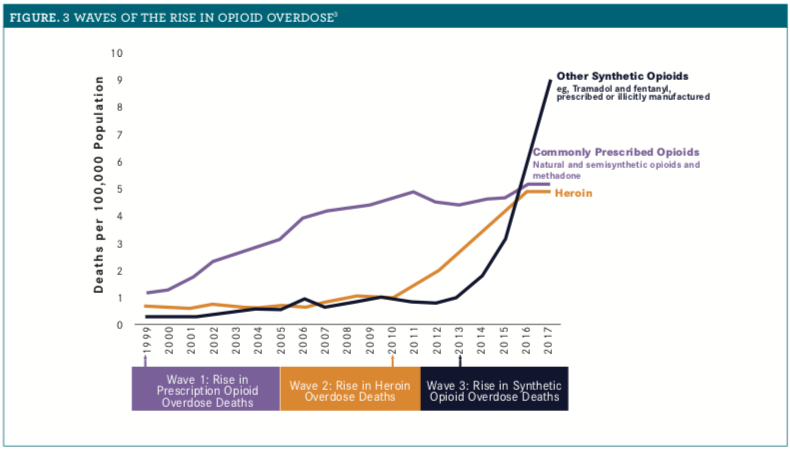

More than 72,000 Americans died of opioid overdoses in 2017, a 10% increase from 2016. It is noteworthy that deaths from the prescription opioids that come readily to mind, such as hydromorphone and oxycodone, have leveled off, whereas deaths from fentanyl and synthetic “illicitly manufactured opioids” have skyrocketed alongside an increase in deaths from heroin (see Figure). We have successfully moved the problem from the pharmacy to cargo ships, drug trafficking routes, and the streets.

Figure.

Look for continued regulatory actions related to effective and safe prescribing and dispensing of opioids to continue to emerge in 2019. Look also for lawsuits to continue to grow in number and scope. But also look toward a pivot in 2019 toward more acceptance of, collaborations, and dollars related to substance abuse treatment. The naloxone dispensing movement was the first phase of thinking of the health care system as part of the solution, not just part of the problem. The next phase will be an effort to create capacity for treatment and substance abuse support. I hope we all get on that train, for moral as well as professional sustainability reasons. Becoming a provider of opioid use disorder and treatment supports may be what our system needs most right now.

Troy Trygstad, PharmD, PhD, MBA, is vice president of pharmacy programs for Community Care of North Carolina. He also serves on the board of the American Pharmacists Association Foundation and the Pharmacy Quality Alliance.

References

- National pharmacy organizations announce new campaign emphasizing the value of our nation’s pharmacists [news release]. Arlington, Virginia: American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. aacp.org/article/national-pharmacy-organizations-announce-new-campaign-emphasizing-value-our-nations. Accessed January 28, 2019.

- National Vital Statistics System Mortality File. 3 waves of the rise in opioid overdose deaths. CDC website. cdc.gov/drugoverdose/images/epidemic/3WavesOfTheRiseInOpioidOverdoseDeaths.png. Accessed January 28, 2019.