Pharmacy Practice in Focus: Health Systems

- March 2014

- Volume 3

- Issue 2

Influenza Season Update

Recommendations for vaccinations vary by age and risk.

Influenza is a contagious respiratory virus that is spread by transmission of respiratory droplets from an infected person, with viral shedding occurring up to 10 days after infection.1 Timing of the influenza season varies, but it typically begins in the fall and can continue through spring, with peak activity normally seen in January or February. The flu is responsible for significant morbidity and mortality, with up to 430,000 hospitalizations and 49,000 deaths attributable to the virus each year.2-4

Epidemiology and Etiology

Influenza affects people of all ages and backgrounds, which is why in 2010 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended that everyone 6 months and older receive the influenza vaccine annually.5 Children younger than 9 years receiving their first influenza vaccine require 2 doses, separated by 4 weeks, to provide sufficient protection.1,5

Populations that are at greatest risk of influenza-related complications are listed in Table 1; however, as in the 2009 outbreak and the current H1N1 outbreak, previously healthy people are also at risk.1,4-6 The flu can result in a spectrum of illness ranging from self-resolving mild disease with symptoms of fever, headache, congestion, body aches, and cough, to severe illness, multiorgan failure, and death. Complications of the flu can include otitis media, sinus infection, viral or bacterial pneumonia, and bronchitis; in severe cases, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation may be employed to provide the heart and/or lungs respite from the severe inflammation and damage caused by the virus.3,4

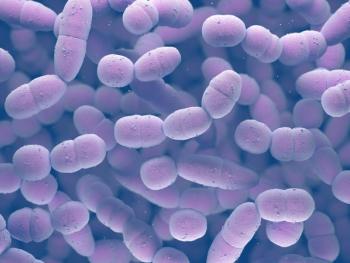

Influenza is characterized by one of 3 single-stranded RNA viruses of the Orthomyxoviridae family: A, B, or C virus.3,4 Influenza A is typically the most common and virulent virus seen in humans, with subtypes named on the basis of 2 glycoproteins found on the surface of the virus: the hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N) proteins. H1N1 and H3N2—the influenza A subtypes currently circulating in humans— are included in the annual influenza vaccine.1,3 B/Yamagata and B/Victoria are the 2 influenza B lineages in circulation; however, before the current 2013-2014 flu season, only 1 of these lineages was included in the annual trivalent vaccine. Given that there is little to no crossreactive protection between the 2 lineages, this resulted in a 50% “mismatch” between the lineage chosen for the vaccine and the lineage present in circulating disease from 2001 to 2010.1,7 With some influenza seasons seeing as much as a 44% influenza B predominance, this “mismatch” and its resulting morbidity led the World Health Organization (WHO) to recommend the inclusion of both influenza B lineages in the annual vaccine for the 2013-2014 flu season.2,8,9

Influenza Prevention

Annual vaccination remains the best method of influenza prevention. However, huge strides are needed to reach the Healthy People 2020 goal of annually vaccinating 80% of children and adults (younger than 65 years) against the flu.10 Each February, WHO recommends the specific strains to include in the vaccine for the following influenza season, with the FDA making the final decision on which strains will be included in the influenza vaccine for the United States.1,4,5 The efficacy of the vaccine varies each flu season, as new strains can appear and current strains can undergo mutation between vaccine development and the beginning of the flu season. Of special note for world travelers—there are 2 influenza seasons and, consequently, the potential exists for requiring 2 influenza vaccines: 1 for the Northern Hemisphere, and 1 for the Southern Hemisphere, depending on whether the strains chosen for each differ.3,4

New Influenza Vaccines

The 2013-2014 influenza season has several novel influenza vaccines, allowing for improved influenza B coverage as well as egg-free options for patients with a severe egg allergy, with vaccine options listed in Table 2. The 2012-approved quadrivalent vaccine is now available in inactivated and live (nasal) formulations. Studies conducted on the quadrivalent formulation thus far have illustrated similar safety and superior immunogenicity for the additional influenza B strain without evidence of compromised antibody response to the 3 strains in the trivalent vaccine.16,17

Compared with a control group of pediatric patients aged 3 to 8 years, use of the quadrivalent vaccine was associated with a decreased incidence of fevers >39°C and a reduction in the development of lower respiratory tract infections.8 In theory, the quadrivalent vaccine should provide superior protection during influenza seasons in which both influenza B lineages cocirculate or when the B lineage present during flu season differs from the lineage circulating during vaccine production. Currently, the CDC does not recommend one flu vaccine product over another, although once the quadrivalent supply can be produced in quantities able to satisfy the population, it is likely to render the trivalent vaccine obsolete.1

Prior to the 2013-2014 influenza season, a type I true anaphylactic allergy to eggs was a contraindication for the influenza vaccine, because the vaccine has traditionally been produced in embryonated chicken eggs. In addition to providing a means for individuals with an egg allergy to receive the influenza vaccine, the non—egg-based formulations are advantageous in that they have a quicker production time and are not dependent on egg supply. Flucelvax is available for individuals 18 years and older and is produced in cultured mammalian cells that are able to be frozen and “banked” to allow for a potentially rapid vaccine turnaround in the event of a pandemic.12 Flublok is available for individuals 18 to 49 years of age and is produced using recombinant DNA and baculovirus expression vector system technology. Unlike other influenza vaccines, this technology allows for inclusion of only the hemagglutinin protein and contains 3 times as much hemagglutinin as conventional vaccines—45 mcg for each of the 3 strains contained in the vaccine.13 Studies have shown its safety and efficacy profile to be similar to that of egg-based influenza vaccines, and studies for both the cell-cultured and the recombinant-DNA formulations are under way to expand the approved age range.12,13

Influenza Treatment

Neuraminidase inhibitor (oseltamivir and zanamivir) is currently the only class of antivirals that exhibits activity against influenza A and B, with dosing information listed in Online Table 3.18-20 Previously, the adamantanes (amantadine and rimantadine) were utilized for influenza A; however, resistance increased over time, and in the 2009-2010 season, 100% of the seasonal and 99.8% of the pandemic H1N1 viruses tested were resistant.19,21 Chemoprophylaxis with neuraminidase inhibitors is not a substitute for annual vaccination but may be of benefit for pre- or postexposure prophylaxis.3,22 Duration of chemoprophylaxis can range from 7 to 10 days after last known exposure to an infected person through the duration of influenza activity in a community.

Online Table 3: Neuraminidase Inhibitor Dosing

Oseltamivir (Tamiflu)22*

Chemoprophylaxis

Treatment

2 weeks to <3 months of age

Not recommended

3 mg/kg twice daily

3 months to <12 months of age

3 mg/kg once daily

(Not FDA approved)

3 mg/kg twice daily

>12 months of age and ≤15 kg

30 mg once daily

30 mg twice daily

>12 months of age and >15 kg to 23 kg

45 mg once daily

45 mg twice daily

>12 months of age and >23 kg to 40 kg

60 mg once daily

60 mg twice daily

>40 kg and Adults

75 mg once daily

75 mg twice daily

Zanamivir (Relenza)23

≥5 years and <7 years of age

10 mg (two 5-mg inhalations) once daily

Not recommended

≥7 years of age and adults

10 mg (two 5-mg inhalations) once daily

10 mg (two 5-mg inhalations) twice daily

*Oseltamivir requires renal dose adjustment in patients with creatinine clearance ≤30 mL/min.

Influenza treatment with antiviral drugs is of most benefit if it is started as soon as symptoms arise, ideally within 48 hours of onset. If treatment is not promptly initiated at symptom onset, there may still be some benefit in initiating a neuraminidase inhibitor outside of the 48-hour window, especially in patients at high risk for complications.

However, careful consideration should be given to each situation in order to protect the susceptibilities of these antivirals. Treatment is typically a 5-day course, although hospitalized patients may receive a longer course.

Oseltamivir is commercially available as a 6-mg/mL suspension and as 30-, 45-, and 75-mg capsules. During the 2009-2010 H1N1 pandemic, oseltamivir had emergency use authorization in children younger than 12 months; in December 2012, the FDA approved its use for influenza treatment in neonates 2 weeks and older.1,23 Oseltamivir chemoprophylaxis is FDA approved in infants 12 months and older, although dosing information is available for younger infants. Oseltamivir is generally well tolerated, with the most common adverse effects being nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.23

Zanamivir is commercially available as a 5-mg powder for inhalation through a breath-activated delivery device. It is FDA approved for prophylaxis in children 5 years and older and for treatment in children 7 years and older.1,24 Due to the risk of bronchospasm following inhalation, zanamivir is not recommended for individuals with underlying lung disease such as asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In addition to the adverse effects shared with oseltamivir, zanamivir can cause cough, headache, arthralgia, bronchitis, and sinusitis.24 An intravenous formulation of zanamivir is currently undergoing phase-3 clinical trials and can be obtained for hospitalized patients through an emergency investigational new drug request to the manufacturer.24

Postmarket reports for both neuroaminidase inhibitors have indicated that children may be at an increased risk for rare neuropsychiatric events resulting in self-harm, including hallucinations, confusion, and delirium.22-24 However, these events are difficult to directly correlate with these medications given that the infection with influenza virus can be associated with behavioral and/or neurologic changes.

Jenna M. Bognaski, PharmD, is a pediatric clinical pharmacist at UNC HealthCare North Carolina Children’s Hospital.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Weekly Rep. 2013;62(RR-07):1-43.

- Wong KK, Jain S, Blanton L, et al. Influenza-associated pediatric deaths in the United States, 2004-2012. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5):796-804.

- Harper SA, Bradley JS, Englund JA, et al; Expert Panel of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Seasonal influenza in adults and children—diagnosis, treatment, chemoprophylaxis, and institutional outbreak management: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(8):1003-1032.

- Clark NM, Lynch JP 3rd. Influenza: epidemiology, clinical features, therapy, and prevention. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;32(4):373-392.

- Committee on Infectious Diseases. Recommendations for prevention and control of influenza in children, 2013-2014. Pediatrics. 2013;132(4):e1089-e1104.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated CDC estimates of 2009 H1N1 influenza cases, hospitalizations and deaths in the United States, April 2009-April 10, 2010. www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/estimates_2009_h1n1.htm. Accessed February 1, 2014.

- Langley JM, Carmona Martinez A, Chatterjee A, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of an inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine candidate: a phase III randomized controlled trialin children. J Infect Dis. 2013;208(4):544-553.

- Jain VK, Rivera L, Zaman K, et al. Vaccine for prevention of mild and moderate-to-severe influenza in children. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(26):2481-2491.

- Ambrose CS, Levin MJ. The rationale for quadrivalent influenza vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012;8(1):81-88.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020. Washington, DC. www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/objectiveslist.aspx?topicId=23. Accessed February 1, 2014.

- Fluzone High-Dose [package insert]. Swiftwater, PA: Sanofi Pasteur; 2013.

- Flucelvax [package insert]. Cambridge, MA: Novartis; 2013.

- Flublok [package insert]. Meriden, CT: Protein Sciences Corp; 2013.

- Fluzone Intradermal [package insert]. Swiftwater, PA: Sanofi Pasteur; 2013.

- Flumist [package insert]. Gaithersburg, MD: MedImmune; 2013.

- Tinoco, JC, et al. Immunogenicity, reactogenicity, and safety of inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine candidate versus inactivated trivalent influenza vaccine in healthy adults ≥18 years: a Phase III, randomized trial. Vaccine. 2014;32:1480-1487. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.022.

- Greenberg DP, Robertson CA, Landolfi VA, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated quadrivalent influenza vaccine in children 6 months through 8 years of age [published online January 17, 2014]. Pediatr Infect Dis J.

- Louie JK, Yang S, Samuel MC, Uyeki TM, Schechter R. Neuraminidase inhibitors for critically ill children with influenza. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):e1539-e1545.

- Ison MG. Antivirals and resistance: influenza virus. Curr Opin Virol. 2011;1(6):563-573.

- Yamamoto T, Ihashi M, Mizoguchi Y, et al. Early therapy with neuraminidase inhibitors for influenza A (H1N1) pdm 2009 infection. Pediatr Int. 2013;55(6):714-721.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update: influenza activity—United States, 2009-10 season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(29):901-908.

- Fiore AE, Fry A, Shay D, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antiviral agents for the treatment and chemoprophylaxis of influenza—recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(1):1-24.

- Tamiflu [package insert]. South San Francisco, CA: Genetech, Inc, 2013.

- Relenza [package insert]. Triangle Park, NC: GlaxoSmithKline, 2013.

Articles in this issue

almost 12 years ago

The Value of a Pharmacy Educationalmost 12 years ago

TBO-Filgrastim (Granix)almost 12 years ago

Multiple Sclerosis Managementalmost 12 years ago

Avoidable ReadmissionsNewsletter

Stay informed on drug updates, treatment guidelines, and pharmacy practice trends—subscribe to Pharmacy Times for weekly clinical insights.